40 Years Ago: STS-41C, the Solar Max Repair Mission – NASA

[ad_1]

On Apr. 6, 1984, space shuttle Challenger took off on its fifth flight, STS-41C. Its five-person crew of Commander Robert L. “Crip” Crippen, Pilot Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, and Mission Specialists Terry J. “TJ” Hart, James D. “Ox” Van Hoften, and George D. “Pinky Nelson flew a seven-day mission that expanded the shuttle’s capabilities. They deployed the Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF), the largest and heaviest shuttle payload up to that time. They retrieved, repaired, and redeployed the failing Solar Max satellite in a highly complex choreography of rendezvous and proximity operations, autonomous astronaut flying of the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), robotic operations, and spacewalking. The mission also demonstrated the ability of the ground teams and astronauts to successfully respond to unexpected situations.

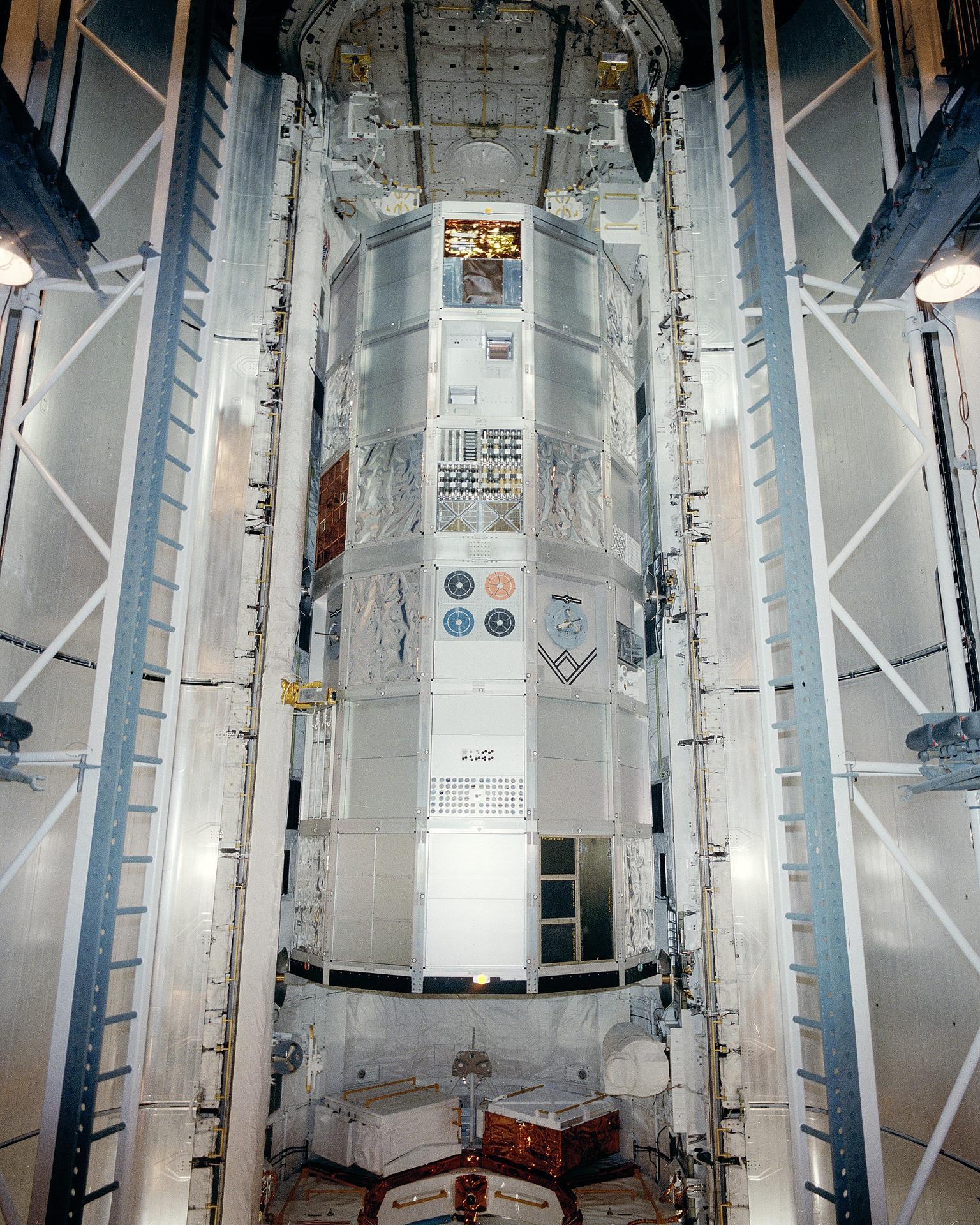

Left: The STS-41C crew of (clockwise from bottom left) Commander Robert L. Crippen, Mission Specialists Terry J. Hart, James D. “Ox” Van Hoften, and George D. “Pinky” Nelson, and Pilot Francis R. “Dick” Scobee. Middle: The STS-41C crew patch. Right: Challenger’s payload bay for STS-41C.

In February 1983, NASA announced Crippen, Scobee, Hart, Van Hoften, and Nelson as the STS-13 crew, the mission renamed STS-41C in September 1983. Crippen, the flight’s only veteran, had flown as the pilot for the first shuttle flight STS-1 in April 1981 and at the time of the announcement in training to command STS-7 in June 1983. For the other four, all selected as astronauts in 1978, STS-41C represented their first trip into space. The mission had two primary objectives. First, the deployment of the LDEF, managed by NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, and second, the retrieval, repair, and release of the Solar Maximum Mission, Solar Max for short, satellite, managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. A student experiment in the middeck looked at the behavior of 3,300 honeybees in weightlessness. Crippen and Scobee had prime responsibility for operating the shuttle and conducting the rendezvous and proximity operations. Hart had primary responsibility for deploying LDEF using the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS), the shuttle’s robotic arm. Nelson would fly the MMU to secure Solar Max so Hart could grapple it with the RMS and place it into a Flight Support Structure (FSS) in Challenger’s payload bay where Nelson and Van Hoften would execute the repairs. Several earlier shuttle flights rehearsed techniques and tested hardware to make STS-41C successful, including the first shuttle spacewalk on STS-6, the SPAS-01 rendezvous and proximity operations on STS-7, the PFTA test of the RMS on STS-8, and the test flights of the MMU on STS-41B.

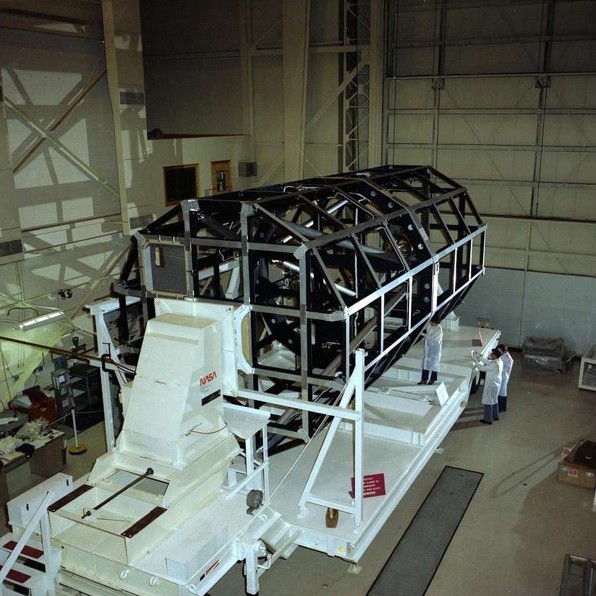

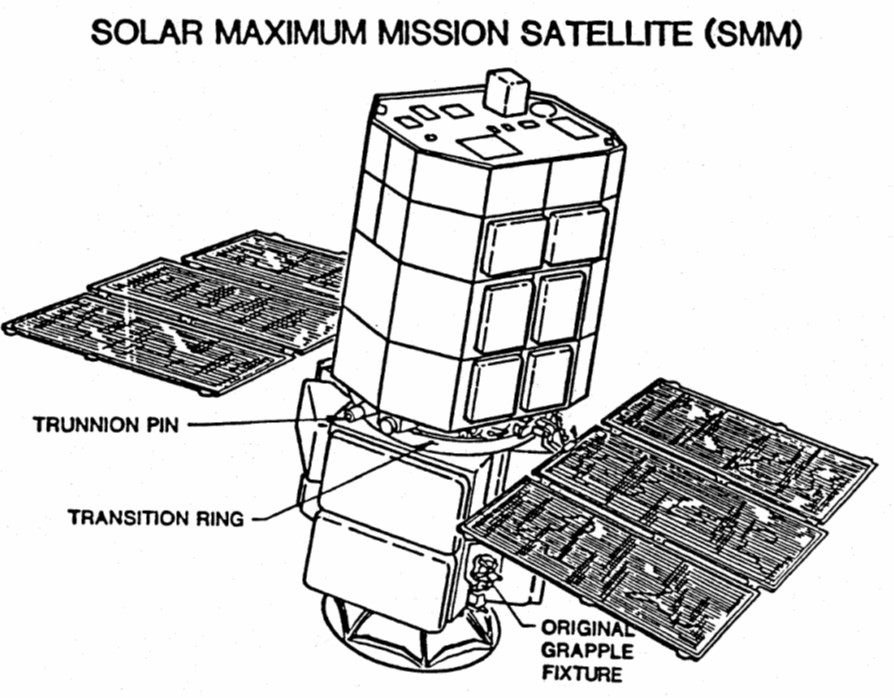

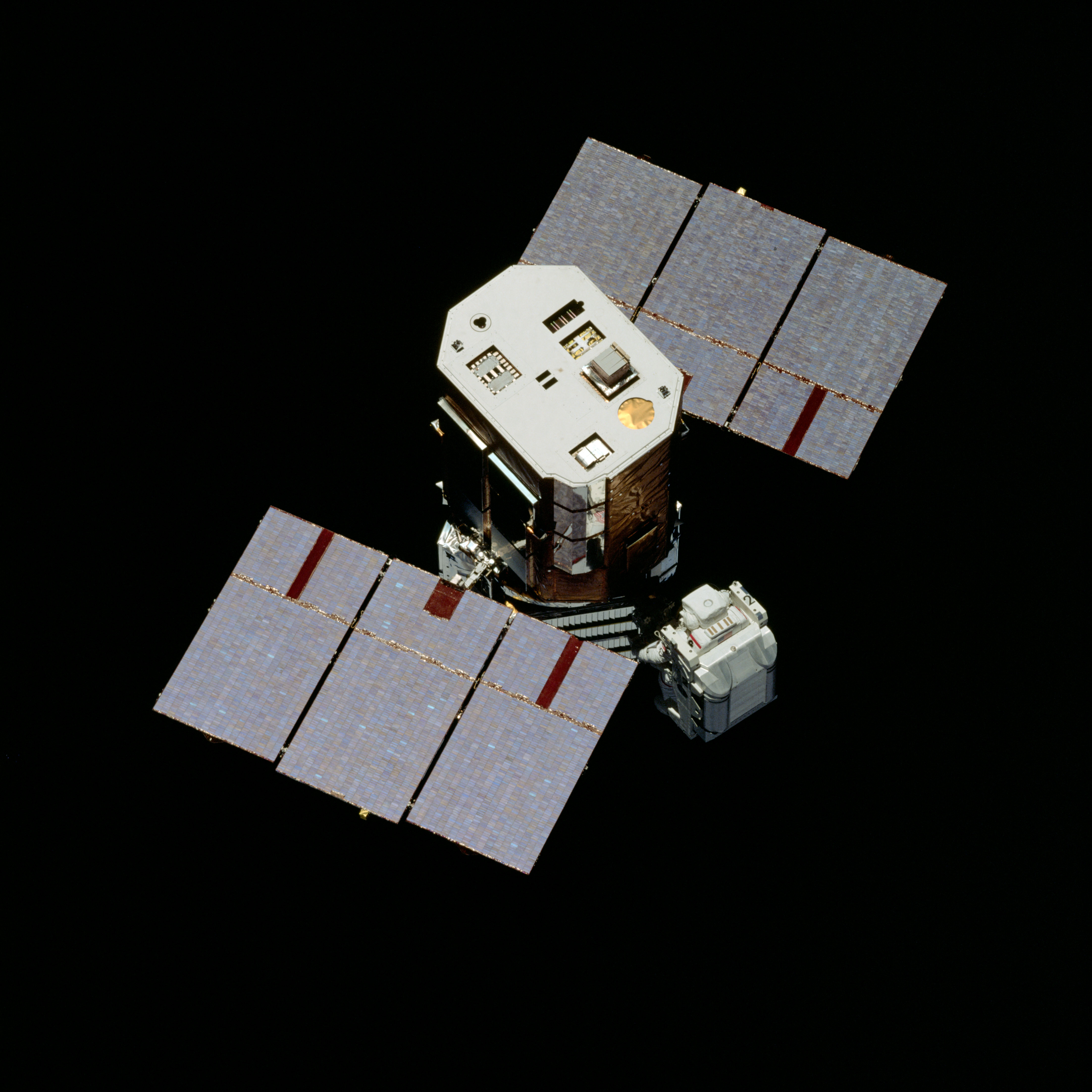

Left: The structure of the Long-Duration Exposure Facility before the installation of the experiments. Middle: Launch of the Solar Maximum Mission in February 1980. Right: Schematic of the Solar Max satellite.

The LDEF consisted of a 21,400-pound structure measuring 14 by 30 feet, at the time the largest and heaviest object launched by the shuttle and handled by the RMS. The satellite contained 86 trays of various types of materials and structures, power and propulsion science, electronics, and optics representing 57 individual experiments managed by 194 U.S. and international principal investigators. A later shuttle mission planned to retrieve LDEF after 9-10 months in orbit and return it to Earth. Solar Max, launched on Feb. 14, 1980, utilized the Multi-Mission Modular Spacecraft body, specifically designed for retrieval by the space shuttle for servicing and/or repair by spacewalking astronauts. One of its instruments, the white-light coronagraph/polarimeter, operated successfully before suffering an electronics failure in September 1980. Two months later, the second of four fuses in Solar Max’s attitude control system failed, causing it to rely on its magnetorquers to maintain attitude. This meant that only three of its seven instruments could obtain useful data, as others required more accurate pointing. Ground controllers put the satellite in a slow spin to keep it in a stable sun-pointed orbit awaiting the arrival of the repair crew. Should the repairs prove unsuccessful, the astronauts could secure Solar Max in Challenger’s payload bay and return it to Earth.

Left: The crawler transporter departs Launch Pad 39A after delivering Challenger. Middle: On launch day, the STS-41C astronauts walk out of crew quarters to board the Astrovan for the ride to Launch Pad 39A. Right: Challenger rises into the sky.

Challenger’s successful first shuttle landing at KSC on Feb. 11, 1984, to end the STS-41B mission shortened the turnaround time between touchdown and the next launch to a then-record 55 days. Following refurbishment and mating with its External Tank (ET) and Solid Rocket Boosters, Challenger returned to Launch Pad 39A on March 29. Liftoff occurred on schedule at 8:58 a.m. EST on April 6, with Challenger taking its five-member crew into the skies. As soon as the shuttle cleared the launch tower, control of the flight shifted to Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, where Flight Director Gary E. Coen led his team of controllers, including capsule communicator or capcom John E. Blaha, monitored all aspects of the launch. STS-41C performed the first direct to orbit ascent, using the shuttle’s main engines to achieve orbit instead of relying on the Orbiter Maneuvering System (OMS) engines to complete the job. The ET reentered over the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii, providing ground observers with a brilliant light show as it broke apart. A later two-minute OMS burn circularized the orbit to reach Solar Max’s 290-mile altitude, the highest of the shuttle program to that time. Once in orbit, the astronauts opened Challenger’s payload bay doors and deployed the Ku-band high-gain antenna to communicate with the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS). They activated and checked out the FSS to support Solar Max in the payload bay and Hart unstowed the RMS and tested its mobility.

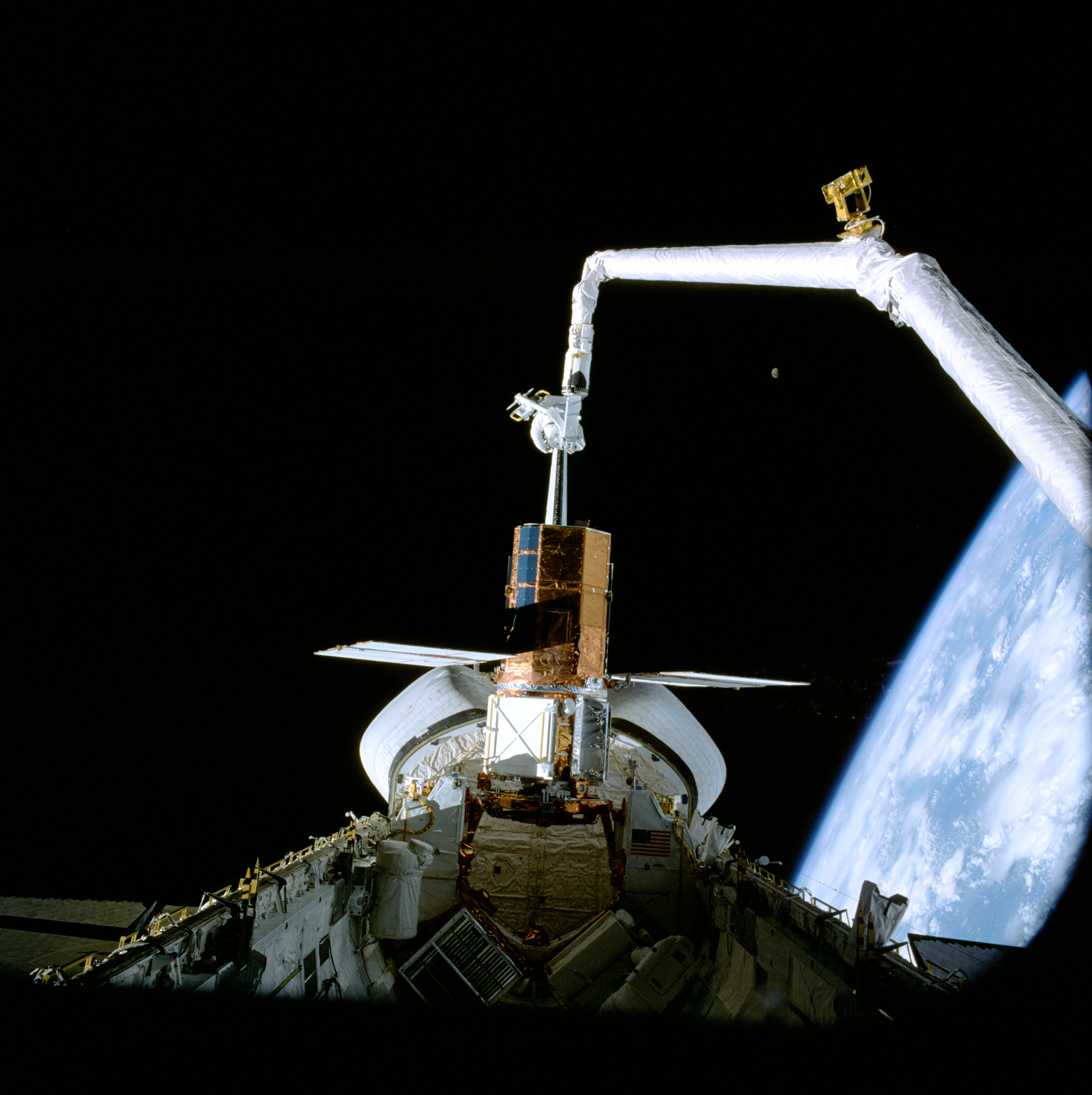

Left: STS-41C astronaut Terry J. Hart lifts the Long-Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) out of Challenger’s payload bay. Middle: LDEF shortly after release. Right: LDEF recedes from Challenger.

The main activity for the astronauts’ second day in space centered around the deployment of LDEF. Crippen undid the retention latches holding LDEF in the payload bay. Hart operated the RMS, grappling LDEF first by the Experiment Initiation System fixture to activate the experiments, then relocating the arm’s end-effector to LDEF’s second fixture to lift it straight out of the payload bay. Holding it high over Challenger, Hart commanded the end effector to release LDEF and Crippen and Scobee pulsed Challenger’s thrusters to slowly back away. LDEF assumed a gravity gradient orientation, with its heavier end pointing at the Earth, remaining stable without the use of any thrusters. To prepare for the next day’s spacewalk, Nelson and Van Hoften began their prebreathe, breathing pure oxygen using their launch and entry helmets, while Crippen reduced the cabin’s pressure from the normal 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi) to 10.2 psi. Due to a configuration issue that had them breathing air instead of oxygen, Nelson and Van Hoften had to repeat the prebreathe activity. They also checked out their spacesuits to ensure their readiness for the spacewalk, while Crippen and Scobee began the series of rendezvous maneuvers to reach Solar Max.

Left: STS-41C astronauts James D. “Ox” Van Hoften, left, and George D. “Pinky” Nelson wear their launch and entry helmets during the prebreathe for the first spacewalk. Middle: Nelson flies the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) from Challenger to Solar Max. Right: Nelson prepares for the first docking attempt with Solar Max.

Mission Control during the first STS-41C spacewalk as NASA astronaut George D. “Pinky” Nelson flies the Manned Maneuvering Unit to the Solar Max satellite.

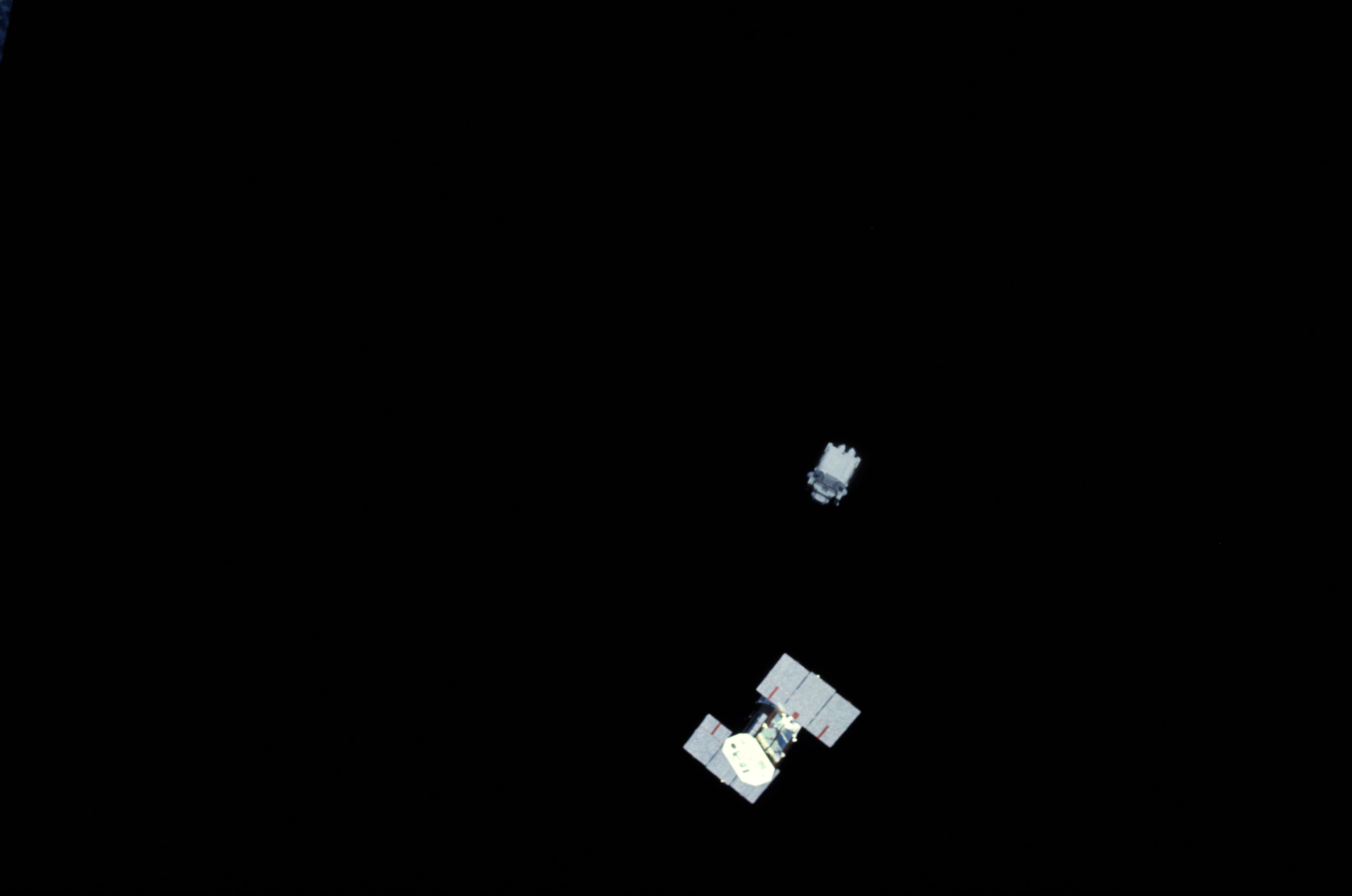

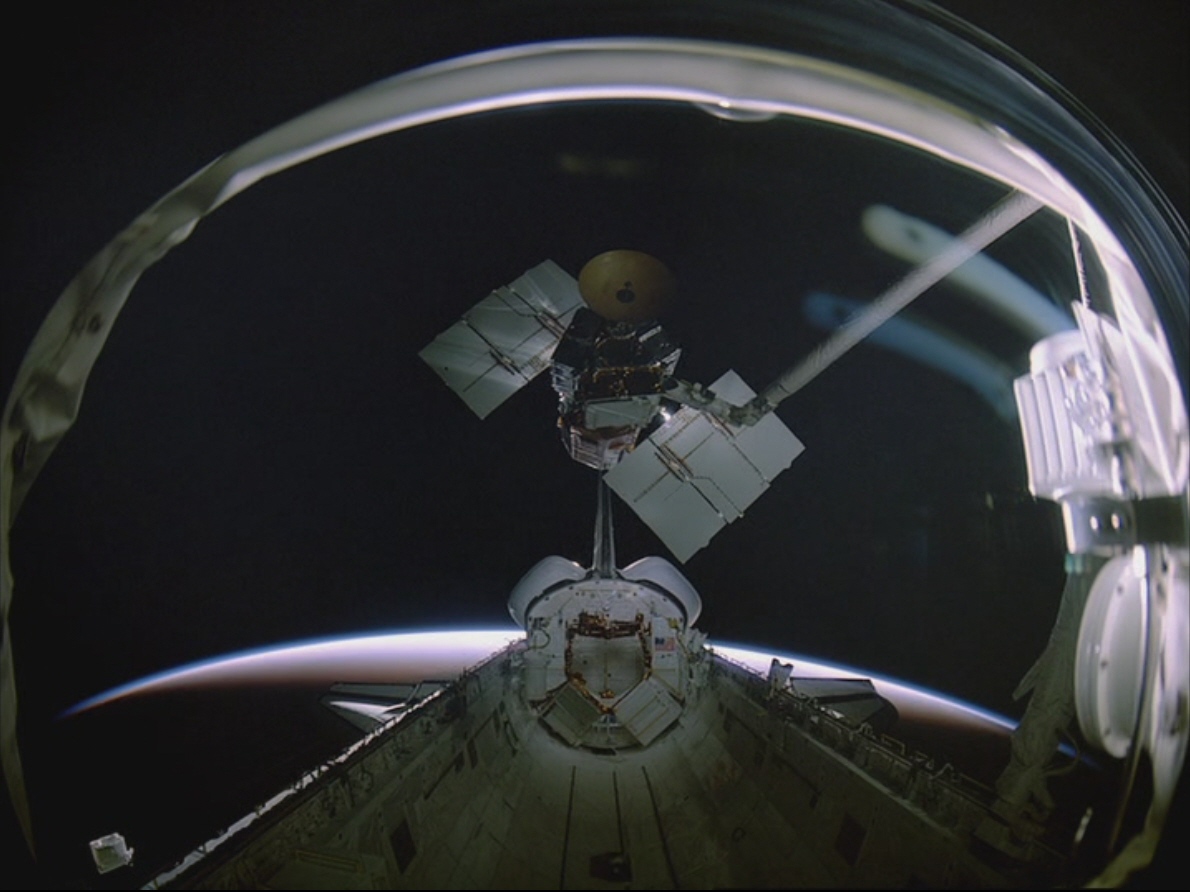

By the time the crew awoke to begin their third day in space, Challenger had closed the distance to Solar Max to 320 miles. Engineers at Goddard powered down Solar Max’s instruments and enabled its communications system to interact with Challenger’s. They also inhibited its attitude control system to allow the astronauts to maneuver it without resistance. The satellite continued its slow rotation of once every six minutes to maintain stability. The astronauts first visually sighted Solar Max at a distance of 600,000 feet, and continued maneuvers to close the distance to the satellite. As Challenger approached Solar Max, Hart assisted Nelson and Van Hoften to don their spacesuits. Jerry L. Ross served as capcom during the spacewalk. Nelson and Van Hoften switched their suits to battery power, officially starting the spacewalk, as Crippen and Scobee closed in on Solar Max, finally stopping 140 feet away. The spacewalkers exited the airlock into the payload bay and began checking out the MMU. Nelson donned the unit and with Van Hoften’s help installed the Trunnion Pin Attachment Device (TPAD), the device used to dock the MMU with a trunnion pin on Solar Max, on the front of the unit. Hart unstowed the RMS, ready to grapple Solar Max. Nelson flew the MMU in the payload bay to familiarize himself with its characteristics then began his 10-minute flight to Solar Max. On his first attempt to dock to the satellite using the TPAD, its jaws didn’t fire to grasp the trunnion pin and he bounced off the satellite. He tried a second time, and once again could not dock. He tried a third time, but bounced off again, his attempts causing Solar Max to wobble in all three axes. He grabbed one of the solar arrays in an attempt to stabilize the satellite. Running low on maneuvering gas, Nelson flew back to the payload bay. Crippen decided to capture Solar Max using the rolling grapple technique with Hart operating the RMS. After several unsuccessful attempts, Mission Control and the crew decided to stand down for the day. Goddard turned on the magnetorquers to slowly bring the spacecraft under control. Nelson parked the MMU, and both he and Van Hoften returned inside after a shortened spacewalk lasting 2 hours 38 minutes. Crippen fired Challenger’s thrusters to back away from Solar Max and station keep 60 miles away overnight. The initial plan for the next day would have Crippen and Scobee rendezvous a second time and have Hart do a rotating grapple with the RMS to capture Solar Max and place it in the FSS, with Nelson and Van Hoften performing the repairs on the satellite during a second spacewalk the day after.

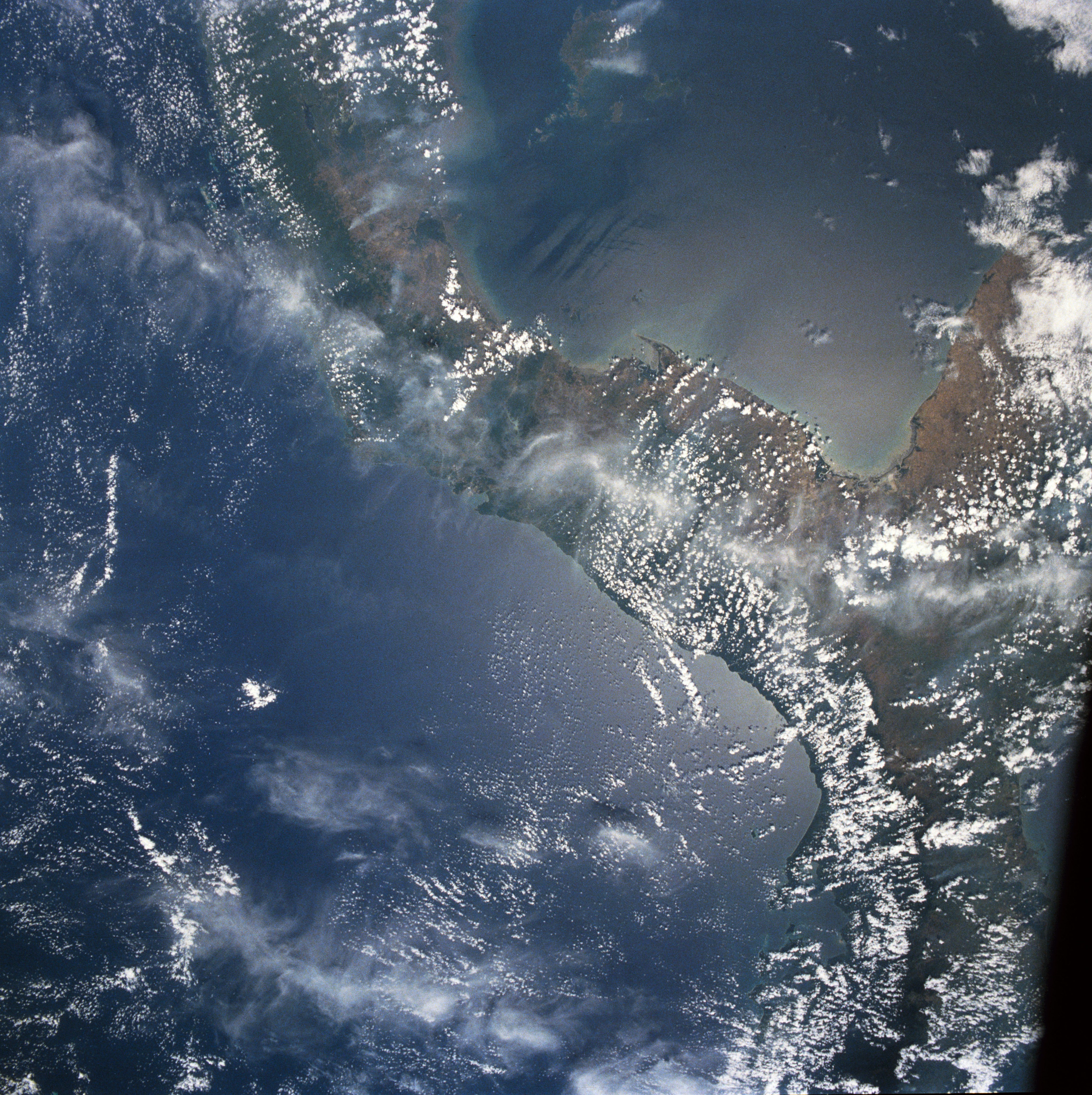

STS-41C crew Earth observation photographs. Left: The Texas Gulf Coast. Middle left: Panama. Middle right: The Richat structure in Mauritania. Right: Circular irrigation in Saudi Arabia.

Overnight, Mission Control decided to take another 24 hours to finalize plans and delayed the rendezvous by one day, adding an extra day to the mission. They informed the crew shortly after the wakeup call on flight day four. In the meantime, engineers at Goddard managed to slow Solar Max’s tumble and pointed its solar arrays to the Sun to charge up its batteries. The crew’s activities on this day focused on the honeybee student experiment, the large format camera, and Earth observations.

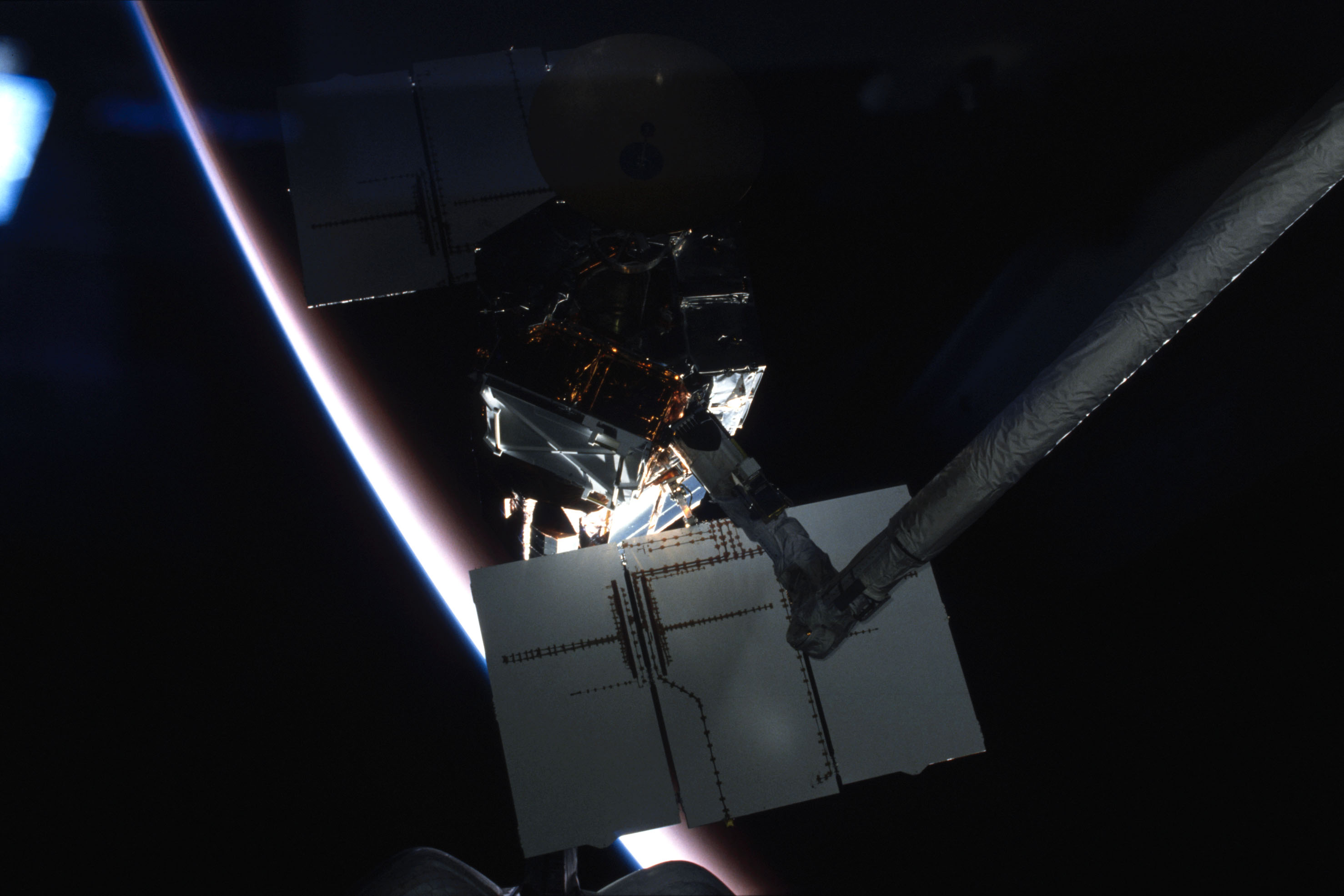

Left: Terry J. Hart grapples Solar Max during orbital night. Right: Using the RMS, Hart moving Solar Max to the Flight Support Structure in Challenger’s payload bay.

The astronauts began their fifth day by starting the second rendezvous with Solar Max, the series of maneuvers bringing Challenger to within 40 feet of the satellite, now rotating at half a degree per second as expected to perform the rolling grapple. With Solar Max positioned over the payload bay, Hart steered the RMS and grappled the satellite on his first attempt. He maneuvered it to the rear of the payload bay and berthed it on the FSS, marking the first in-orbit capture of a satellite for repair. Umbilicals provided power from the shuttle to Solar Max. Hart unlatched the RMS and stowed until its next use during the following day’s spacewalk. President Ronald W. Reagan called to congratulate the crew on the successful capture of Solar Max.

Left: Astronauts George D. “Pinky” Nelson, left, and James D. “Ox” Van Hoften replace Solar Max’s attitude control system module during the second STS-41C spacewalk. Middle: Van Hoften, left, and Nelson replace the main electronics box of one of the satellite’s instruments. Right: Nelson on the end of the Remote Manipulator System inspects Solar Max.

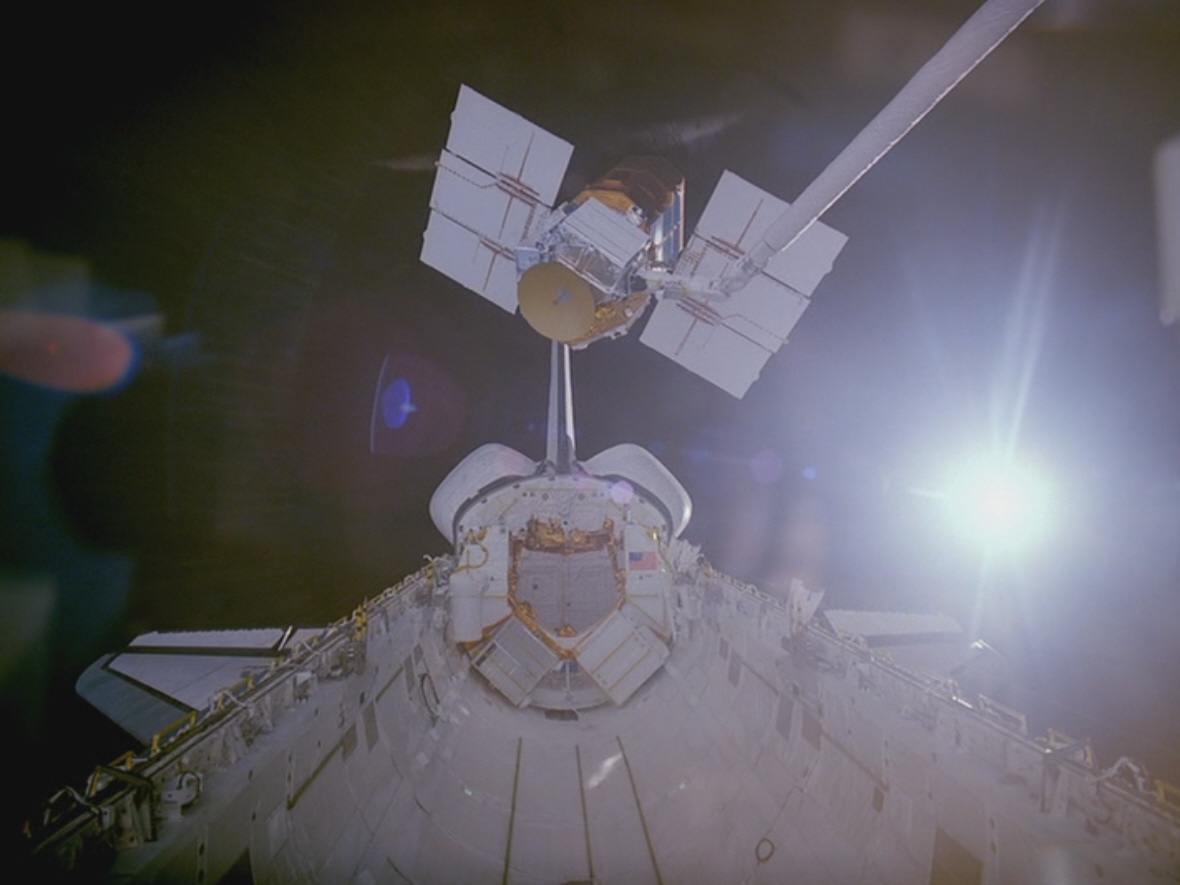

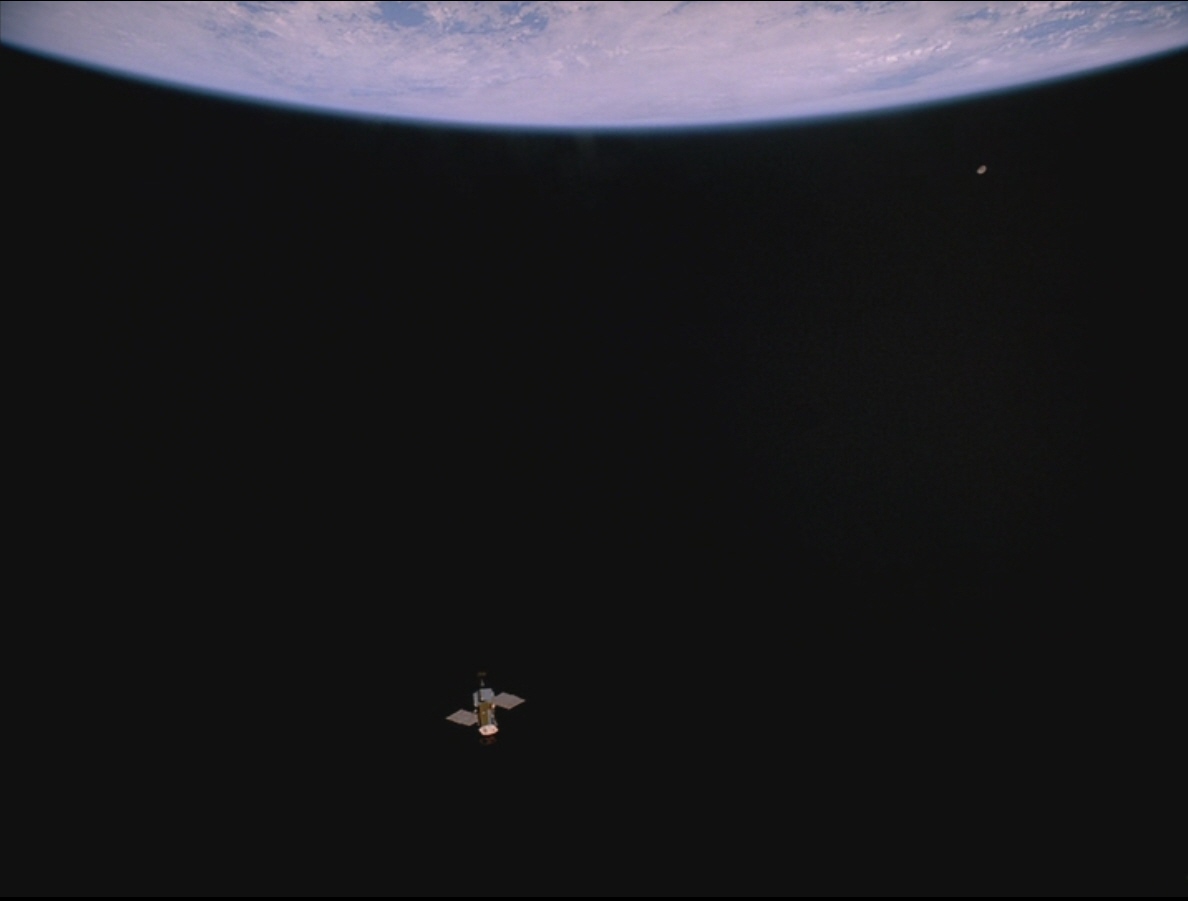

Left: During the second STS-41C spacewalk, James D. “Ox” Van Hoften flies the Manned Maneuvering Unit in Challenger’s payload bay. Middle: Terry J. Hart lifts the repaired Solar Max out of Challenger’s payload bay. Right: Solar Max departs from Challenger.

On flight day six, Scobee helped Nelson and Van Hoften put on their spacesuits in preparation for the mission’s second spacewalk, with the plan to complete all the repairs on Solar Max originally planned across two excursions. After depressurizing and exiting the airlock, Van Hoften positioned himself on the Manipulator Foot Restraint (MFR) that Hart had picked up with the RMS. With both spacewalkers back with the Solar Max, they first replaced the satellite’s attitude control system module – the item that crippled the satellite – in just 45 minutes. They next installed a manifold to protect the X-ray polychromator instrument. For the final task, the replacement of the main electronics box of the satellite’s chronograph polarimeter instrument, never designed for on-orbit repair, Nelson swapped places with Van Hoften on the MFR. The two completed that task in one hour. Nelson then moved over to take measurements of the trunnion pin to determine why the TPAD could not latch onto it during the first spacewalk. He noted a little thermal button sticking up about ¼ inch that might have interfered with the TPAD, later identified conclusively as the culprit. Hart then steered Nelson on the end of the arm to conduct a survey of Solar Max. Because the spacewalkers completed the repair tasks ahead of schedule, Mission Control allowed Van Hoften to fly the MMU in the payload bay and conduct engineering tests with it. Nelson and Van Hoften returned to the airlock, ending the second spacewalk after 6 hours 44 minutes, the longest Earth orbital spacewalk to that time. Between the two spacewalks, Nelson and Van Hoften spent 9 hours 22 minutes outside Challenger. Hart grappled Solar Max with the RMS and lifted it out of the FSS, holding it over the payload bay overnight as engineers at Goddard checked out the satellite’s systems prior to release the next day.

Left: STS 41C astronaut James D. “Ox” Van Hoften examines the honeybee student experiment. Right: The STS-41C crew members pose on Challenger’s flight deck near the end of their successful mission, wearing customized shirts.

The next morning, Hart released Solar Max from the RMS and Scobee flew the shuttle away from the satellite. Later in the morning, the astronauts, sporting shirts that read “Ace Satellite Repair Co.,” held a 30-minute press conference, answering reporters’ questions about their ultimately successful first repair of an on-orbit satellite. They spent the rest of the day readying Challenger for the next day’s entry and landing, including stowing unneeded equipment and testing the orbiter’s maneuvering thrusters and aerodynamic control surfaces. Nelson and Van Hoften stowed the two spacesuits and Hart the RMS, equipment that had served the crew so well during this mission.

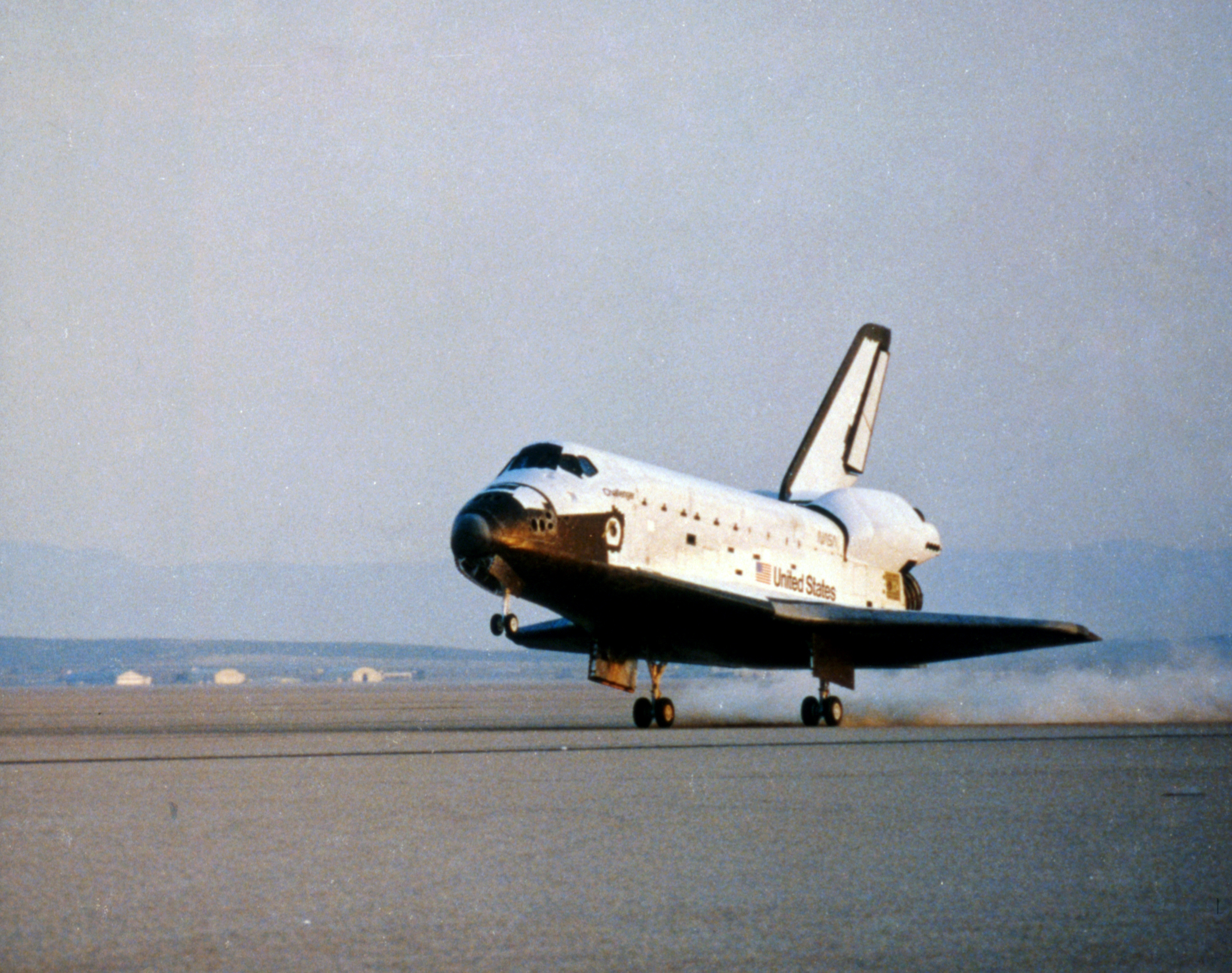

Left: Space shuttle Challenger rolls down the runway at Edwards Air Force Base in California to end the STS-41C mission. Middle: STS-41C astronauts congratulate themselves on a successful flight. Right: In Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Lead STS-41C Flight Director Eugene F. Kranz applauds the successful landing of STS-41C.

On Friday April 13, as the astronauts awakened for their final day in space, their distance to LDEF had increased to more than 6,000 miles and to Solar Max to 80 miles. In preparation for reentry, the astronauts closed the payload bay doors. Mission Control called up that a low cloud deck had moved over the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at KSC and waved off the deorbit burn by one revolution. As the weather at KSC worsened, with light rain showers moving in, Mission Control decided to bring Challenger home at Edwards Air Force Base in California, where the weather seemed perfect. Crippen and Scobee oriented Challenger with its tail in the direction of flight and fired its two OMS engines to slow the spacecraft enough to drop it from orbit. They reoriented the orbiter to fly with its heat shield exposed to the direction of flight as it entered Earth’s atmosphere at 400,000 feet. The buildup of ionized gases caused by the heat of reentry prevented communications for about 15 minutes but provided the astronauts a great light show as their reentry took place in darkness. After crossing the California coastline, they made the final turn into Edwards. Scobee lowered the landing gear at 300 feet and Crippen brought Challenger down to a smooth touchdown 16 minutes after sunrise on Edwards’s dry lake bed runway 17, calling out “Houston, Challenger is wheels stop,” to end the successful satellite deployment and repair mission. During the mission lasting 6 days 23 hours 40 minutes they orbited the Earth 108 times.

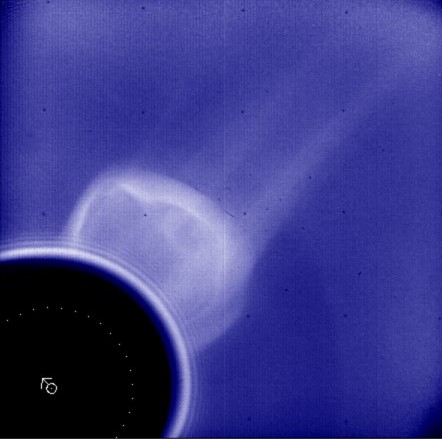

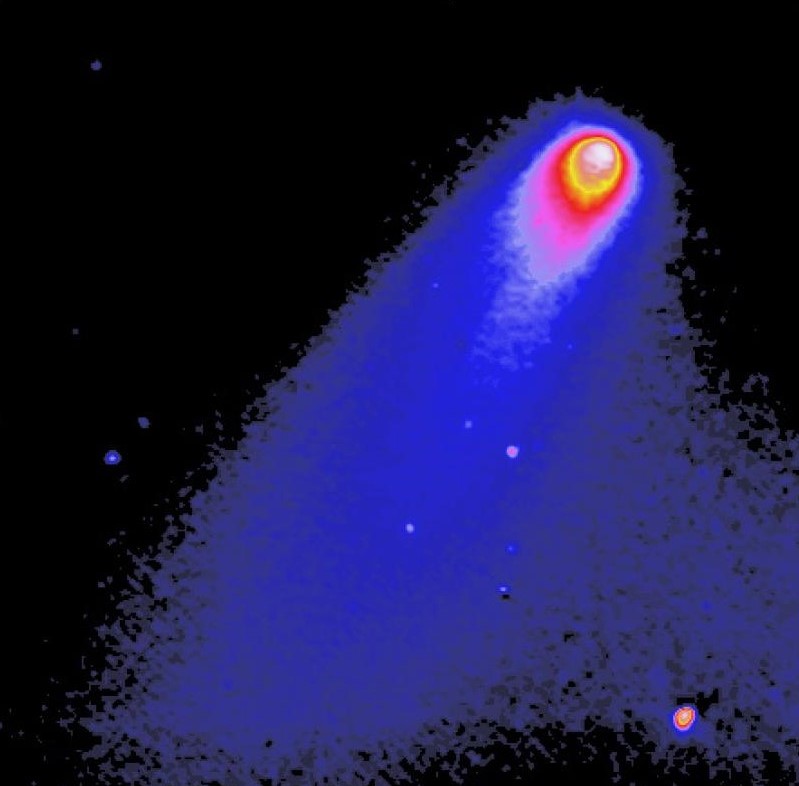

Left: Space shuttle Challenger arrives back at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft. Middle: Solar Max image of a solar coronal mass ejection event on May 4, 1986. Right: Solar Max false color image of Halley’s comet taken on Feb. 28, 1986.

Following the landing, the astronauts returned to Houston, where they reunited with their families who had awaited them at KSC. Workers at Edwards towed Challenger to NASA’s Dryden, now Armstrong, Flight Research Center and mounted it atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a modified Boeing 747. On April 17, the duo took off from Edwards on the first leg of the transcontinental flight to KSC. After an overnight refueling stop at Kelly AFB in San Antonio, Challenger arrived at KSC’s SLF, where workers began preparing it for its next flight, STS-41G. Meanwhile, engineers at Goddard began activating Solar Max’s instruments almost immediately after deployment, and all systems, including the repaired ones, worked perfectly, and within three days its instruments began collecting science data. Following a 30-day thorough checkout, Solar Max returned to a fully operational status. And although it missed the 1980 solar maximum, the satellite returned much useful data as the Sun cycled through a solar minimum and approached the next maximum in the 11-year cycle. When the mission ended in November 1989, Solar Max had returned 240,000 images of the Sun’s corona, recorded more than 12,000 solar flares, and observed 15 deep-space gamma ray bursts and also observed Halley’s Comet as it passed through the inner solar system in early 1986. Although planned for retrieval after 9-10 months in space, LDEF remained in orbit far longer. A series of payload shuffles in 1985 followed by the Challenger accident in January 1986 and subsequent extended grounding of the shuttle fleet delayed its return until STS-32 in January 1990, after 57 months in space.

Enjoy the crew narrated video of the STS-41C mission.

Read Crippen’s, Hart’s, Van Hoften’s, and Nelson’s recollections of the STS-41C mission in their oral histories with the JSC History Office.

[ad_2]