Malaspina Glacier in a Riot of Color

[ad_1]

Today’s story is the answer to the November 2023 puzzler.

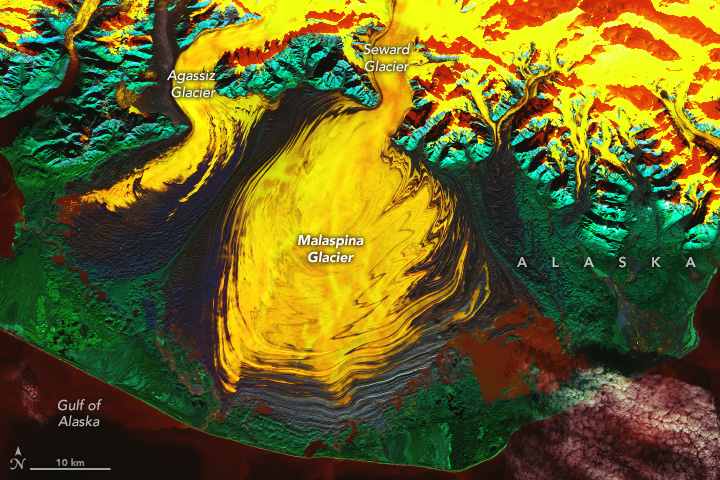

To human eyes, glacial ice typically looks white tinged with blue. But in this false-color satellite image, the rippled ice of Alaska’s Malaspina Glacier appears more fiery than frosty.

This view of Malaspina Glacier on the southeastern coast of Alaska was captured by the OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager-2) on Landsat 9 on October 27, 2023. The coastal/aerosol, near infrared, and shortwave infrared bands are displayed here: a band combination of 1-5-7. In this configuration, watery features are displayed in reds, oranges, and yellows; vegetation appears green; and rock is shown in shades of blue.

The sprawling Malaspina Glacier—or Sít’ Tlein, Tlingit for “big glacier”—is located mostly within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. At approximately 1,680 square miles (4,350 square kilometers) in size, it is the world’s largest piedmont glacier and covers an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. Its main source of ice is the Seward Glacier, which spills out of the St. Elias Mountains onto a broad coastal plain. Several other glaciers, such as the Agassiz, also fan out onto this plain and coalesce to form the larger Malaspina.

The dark blueish-purple lines on the ice are moraines—areas where soil, rock, and other debris have been scraped up by the glacier and deposited along its edges. The zigzag pattern of the debris is caused by changes in the ice’s velocity. Glaciers in this area of Alaska periodically “surge” or lurch forward for one to several years. As a result of this irregular flow, the moraines can fold, compress, and shear to form the characteristic textures seen on Malaspina.

At the terminus, or end, of the glacier, a thin strip of land creates a barrier between the ice and the Gulf of Alaska. A comparison of satellite imagery over time has revealed a lagoon system forming along that barrier over the past few decades. Small patches of open water are visible here in a rusty red color. Some of this water is nearly as salty as the ocean, according to recent research, meaning that comparatively warm ocean water is making contact with the ice. This could lead to large-scale calving and hasten the glacier’s retreat.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Lindsey Doermann.

[ad_2]