As Holocaust education becomes compulsory in some provinces, advocates call for wider adoption | CBC News

[ad_1]

Marilyn Sinclair says she’s feeling “pretty great” about Ontario’s new requirement that sixth-graders learn about the Holocaust.

Sinclair, founder of Holocaust education organization Liberation 75, is responding to more than 8,000 requests for copies of a book from Grade 6 teachers across the province. Told from a child’s perspective, the book recounts the real-life story of the St. Louis, a ship filled with Jewish refugees that fled Nazi Germany in 1939 and was turned away from Cuba, the U.S. and Canada.

The free books from Sinclair’s organization will also come with a toolkit of teaching resources, information about a forthcoming speaker series with the author, and links to an online “book club” where educators can trade teaching strategies.

“[The package] was our way of saying, ‘Don’t be scared, we’re here. We’re going to provide you with the resources you need,'” Sinclair said. “Teachers have a lot to teach in the curriculum. We want to make it as easy and as pleasant for them as possible.”

She stresses that the books and educational materials take an age-appropriate approach.

“We are not talking about gas chambers. We’re not talking about mass genocide,” she said. Instead, they will be “introducing students to the idea of what it means to be othered, what it means to be separated from parents, what it means to be treated badly in some cases, for people to stand up for you in other cases.”

Featured VideoOntario and British Columbia will update their high school curriculum by the 2025 school year in an effort to combat antisemitism. B.C. says it will make it mandatory for Grade 10 students to learn about the Holocaust while Ontario will expand its current Holocaust curriculum.

Sinclair is part of a dedicated chorus of educators, school officials and cultural groups across the country that has for years called on provincial governments to make learning about the Holocaust — the systemic, mass killing of six million Jews in Europe during the Second World War — a mandatory part of Canadian students’ education.

With Ontario and British Columbia moving to embed lessons about the Holocaust in the school curriculum, these advocates are now eager to get started on the implementation process. Meanwhile, elsewhere in Canada, those who hope to follow suit say they’re still waiting for a similar commitment from their provincial governments.

‘Strengthening fundamental knowledge’

A year after he added the topic to the Grade 6 social studies curriculum, Ontario Education Minister Stephen Lecce this week unveiled plans to expand and build upon what students learn about the Holocaust in Grade 10 history.

Ontario’s expanded curriculum component for high schoolers isn’t slated to roll out until the 2025-26 school year, in order to give secondary teachers more time to boost their knowledge and confidence in tackling the subject with sensitivity, Lecce said.

The intention is to incorporate discussion of extreme political ideologies, as well as antisemitism in Canada during the 1930s and ’40s and in contemporary times.

“This is about building capacity as a society to stand up against all forms of hate,” Lecce said in an interview with CBC News on Thursday. “Hate that starts with the Jewish people, as history shows, never ends with the Jewish people. This is a threat to all of us.”

Earlier in the week, B.C. Premier David Eby committed to make Holocaust education mandatory for his province’s Grade 10 students, beginning in 2025-26.

“It is critical that when we’re talking about injustices — when we’re teaching kids about injustices and history in Grade 10 — that they learn about the Holocaust,” Eby said at Monday’s announcement.

Lesson plans, resources, teacher supports required

Nina Krieger, executive director of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, has long worked with educators who choose to explore the Holocaust with their students: diving into topics such as critical thinking, social responsibility, human rights, and roles and responsibilities at a time of moral crisis, she said.

There’s been a greater demand for the centre’s expertise from B.C. educators in recent years, she added, as officials respond to antisemitic incidents at schools — taunts in class or graffiti in playgrounds, for instance — and a proliferation of antisemitism on social media.

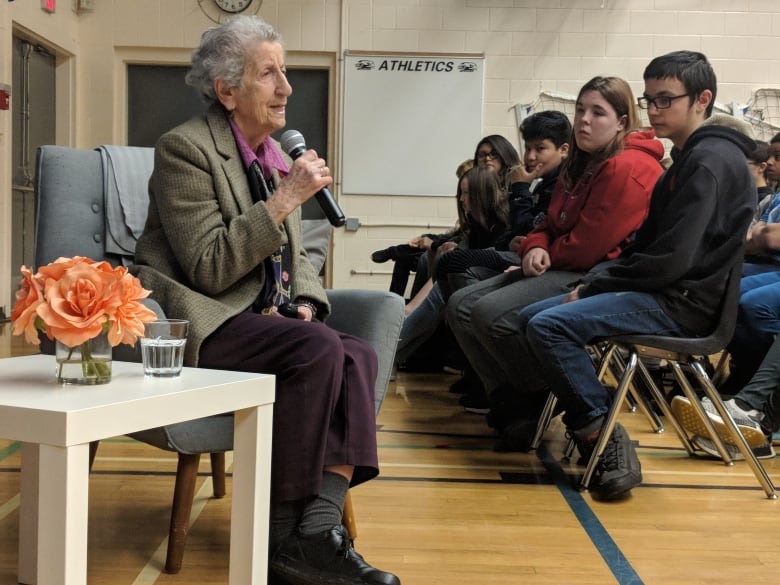

Over the years, Krieger and her team have created professional development and teacher-training sessions, spent time at teacher conferences and engaged with senior educators, who then share knowledge with colleagues. They also developed engaging resources and programs (online and in-person) that directly link to what students are learning in their classes. The education centre has also welcomed myriad students into exhibits, workshops and talks with Holocaust survivors.

However, with the Holocaust becoming mandatory learning in B.C., there’s an even greater need for robust tools and training so that teachers can successfully bring it to students, she said.

“It will require investment in terms of the development of a curriculum, of lesson plans, resources and, critically, supports for educators,” she said. “This is a very daunting topic to teach.”

Krieger’s team will be among the groups developing B.C.’s curriculum update. She says she’s looking forward to getting started, as well as learning from and collaborating with Ontario colleagues who are doing the same. She’s also hoping to pay it forward by supporting educators in other Canadian provinces or territories that might adopt this mandate.

“We sincerely hope that there will be more.”

Holocaust education is already a priority for the English Montreal School Board, which programs special events and activities for teachers and students across the board. However, a provincial mandate that embeds it in the curriculum as a compulsory topic would go much further, says board chair Joe Ortona.

At the moment, he says, Quebec educators have the option of teaching about the Holocaust, and it can be challenging for those who choose to teach it to work it into the curriculum when that means something else will have to be cut in turn.

The board passed a resolution on Oct. 3 calling on the Quebec government to make Holocaust education compulsory in elementary and high schools, but according to Ortona, the province hasn’t responded.

“That’s really unfortunate, because it’s clearly demonstrated that there are advantages to this education being open to all Quebecers,” he said. He adds that research has shown learning about the Holocaust decreases hate incidents against Jewish people as well as those from other marginalized groups.

“That’s a good thing because that is essentially what we’re striving for: a more diverse, inclusive, tolerant society, where everybody is made to feel welcome,” he said. “And so we think this obviously helps meet that objective.”

[ad_2]