‘Cold and with a lot of calculation’: 2020 ambush of deputies was revenge for slain friend

[ad_1]

By the time he sidled up to a patrol car and shot two Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies at point-blank range, Deonte Lee Murray was in the midst of a crime rampage.

It began 11 days earlier, when he shot a man in Compton and stole his Mercedes-Benz, Deputy Dist. Atty. Stephen Lonseth told a jury Wednesday in his closing argument at Murray’s trial on charges of attempted murder, assault, robbery and carjacking. It escalated when Murray’s best friend was killed in a fiery confrontation with sheriff’s deputies.

Seeking revenge, Lonseth said, Murray shot a man outside the Compton courthouse whom he mistook for a detective. Angered the shooting didn’t make the news, the prosecutor said, Murray targeted the two deputies, Claudia Apolinar and Emmanuel Perez-Perez, as they sat in a patrol car parked at a Metro station. Lonseth called it a “miracle” the deputies weren’t killed.

His argument to the jury came just four days after another sheriff’s deputy, Ryan Clinkunbroomer, was shot to death inside his patrol car in Palmdale in what authorities have described as a similarly unprovoked ambush. Prosecutors on Wednesday charged a 29-year-old Palmdale man, Kevin Cataneo Salazar, with the deputy’s murder. Cataneo Salazar has pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity.

Murray, who testified in his own defense, admitted shooting all four people. His lawyer, Kate Hardie, told the jury the only question was intent. She argued that Murray, blinded by grief over his friend’s death and on a sleepless, two-day binge of cognac and methamphetamine, was acting on impulse when he pulled the trigger.

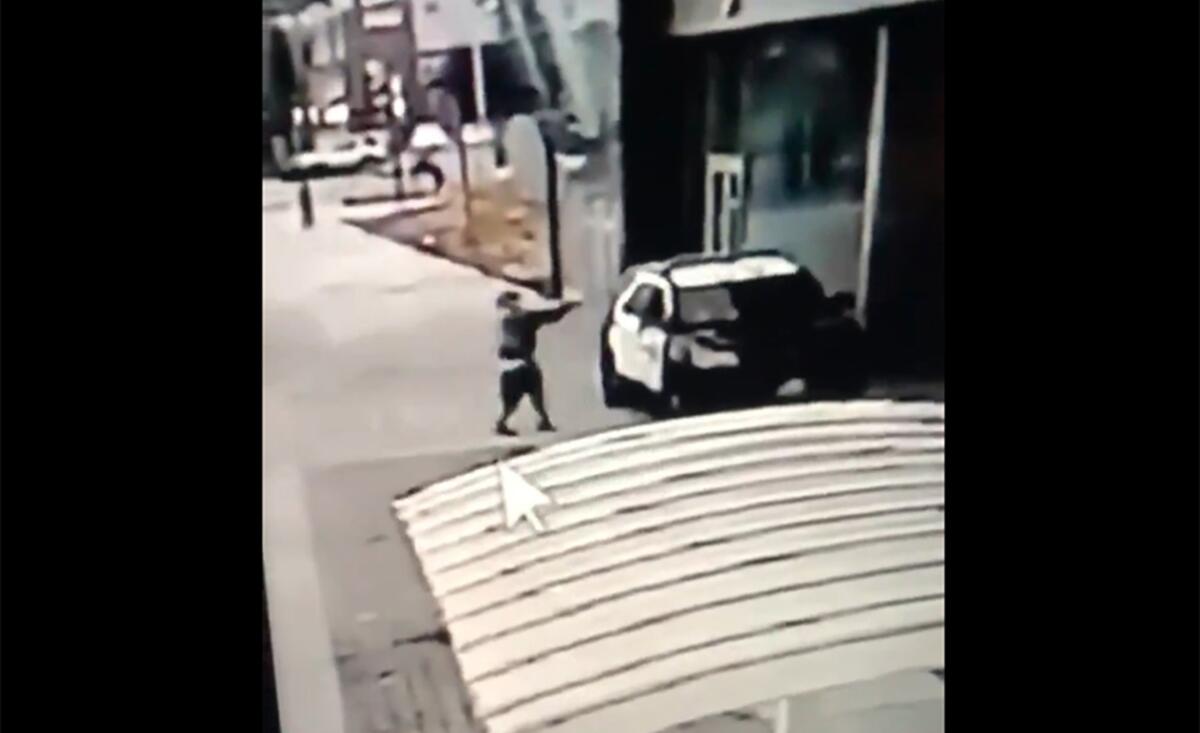

Video released by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department shows a gunman walking up to sheriff’s deputies and opening fire without warning or provocation in Compton.

(Associated Press)

“When you dig below the surface,” she said, “you can see this wasn’t premeditated.”

The jury began deliberating Wednesday afternoon. Superior Court Judge Connie Quinones barred The Times from photographing Murray, 39, after his lawyer argued it would expose him to attacks in jail.

Murray’s crimes began on Sept. 1, 2020, when he pointed an assault rifle at an acquaintance, Andrew Harris, and demanded the keys to his Mercedes, Lonseth said. After Harris dropped the keys, Murray shot him in the leg and drove off in the car — the one “he did all the dirt with,” Lonseth told the jury.

Murray claimed he had won the black sedan in a dice game. He confronted Harris, angry that he’d not only refused to hand over the car but that he was spreading a rumor that Murray was involved in the death of a woman, Hardie said.

Nine days later, sheriff’s deputies surrounded the home of Murray’s best friend, Samuel Herrera, before dawn. As they prepared to serve a search warrant, several deputies would later tell prosecutors, they heard Herrera loading a gun inside the Bradford Street home’s garage and yell that he was going to “shoot it out.”

The deputies started shooting. By the time it was over, the garage had caught fire, and Herrera lay dead, shot 10 times, according to a coroner’s report. Deputies found six rifles and a handgun inside the charred garage, according to the district attorney’s analysis of the incident.

Hardie described Herrera as the “one pillar” in Murray’s life at a time when it seemed like it was coming apart. The mother of his children had kicked him out. Living out of his car, he spent much of his time driving around aimlessly, she said.

Murray claimed that, after Herrera was killed, he saw deputies exchanging high-fives outside the home. He showed up to the family’s vigil with a bottle of Hennessy and spent the next 48 hours in “a blur,” drinking and using methamphetamine, his lawyer said.

Murray drove the stolen Mercedes past the Compton courthouse, where he spotted a man sitting inside a silver Ford Explorer. Assuming he was a plainclothes detective, Murray raked the SUV with an assault rifle, hitting it five times, Lonseth said.

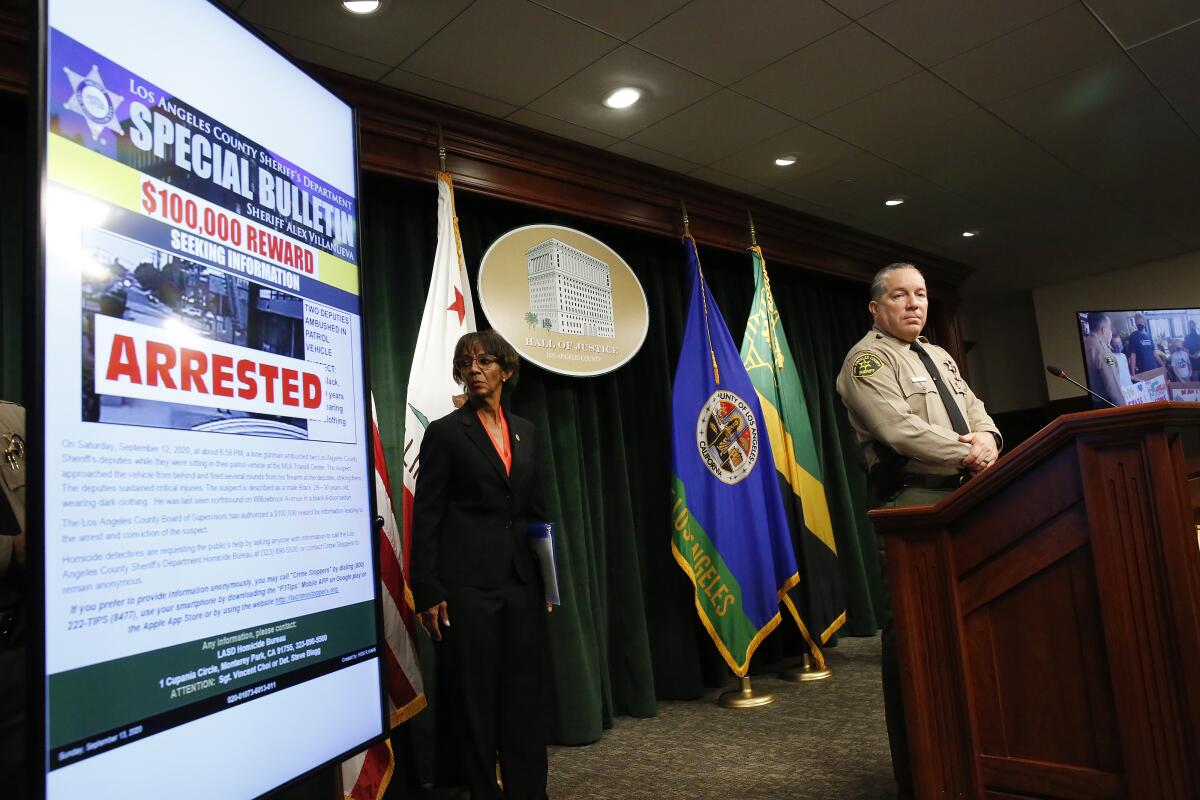

Then-Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva and then-Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey announce the arrest of Deonte Lee Murray in the ambush shooting of two deputies.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

The man was no detective — he’d gone to the courthouse to file some paperwork and was “trying to do a Zoom meeting in his car,” Lonseth told the jury.

Murray told a friend he was angry the shooting hadn’t made the news, Lonseth said. That evening, he drove to a Blue Line stop in Compton, just a few hundred yards from the courthouse, where Apolinar and Perez-Perez were stationed in a patrol car.

A surveillance camera at the train stop captured Murray approaching the cruiser, “not running, not doing anything impulsively, but cold and with a lot of calculation,” Lonseth said. He shot both deputies through the front passenger’s window before running away. The footage showed Apolinar, the front of her khaki uniform dark with blood, tending to her partner’s wounds until a fleet of patrol cars arrived.

“They’re alive because of, frankly, a miracle, and the heroics of Claudia Apolinar, who, despite being shot through the jaw, through the wrist, kept this from being a murder case,” Lonseth said.

According to Lonseth, Murray bragged to witnesses that he “smoked those m—s” and expressed shock when he learned they’d lived, telling one woman, “Can you believe that sh—?”

When the police moved in to arrest him three days after the shooting, Murray bolted, tossing away a .40-caliber handgun that was found to have been used to shoot the deputies, Lonseth said.

“Who is Deonte Murray?” the prosecutor asked the jury. “This is a man that shot four people, that tried to kill three of them, including two deputy sheriffs that he ambushed. This is a man who will do anything.”

[ad_2]