Drought Fuels Wildfires in the Amazon

[ad_1]

In the absence of human activity, fires would not burn in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. It’s too wet, even during the driest parts of the year. Yet for as long as satellites have made large-scale monitoring of the rainforest possible, researchers have observed thousands of fires in the Amazon every year, with especially intense activity during the dry months of July through November.

2023 is no exception. Satellite observations from several fire monitoring platforms, including the SERVIR Amazon Fire Dashboard, the Brazilian Space Agency’s Queimadas program, and NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System have detected large numbers of fires burning throughout the Amazon basin since the start of the year. They have also observed particularly intense fire activity in September and October in the northern and western Amazon as drought tightened its grip on the region.

Every year, people intentionally light large numbers of fires in the Amazon basin. Often, the goal is to clear forests or manage crops and pastures, though there are an array of other reasons including burning trash or starting cooking fires. Some fires are unintentional ignitions associated with human activity, including discarded cigarettes or sparks from electrical or farming equipment.

In 2023, as researchers forecasted months in advance, the peak of fire season coincided with an ongoing El Niño and a drought in the northern and western part of the basin that worsened the burning. Outbreaks of fire were particularly intense in Amazonas, Para, and Amapá, according to satellite observations. In these areas, drought conditions followed by hot and dry weather have enlarged fires that would have otherwise been unable to spread.

The MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) sensor on NASA’s Terra satellite captured an image (top of the page) showing smoke streaming from fires burning near Manaus on October 11, 2023. The city, a transportation and manufacturing hub deep in the rainforest, is the capital city of Brazil’s Amazonas state. Smoke from the fires periodically engulfed the city of two million in September and October, at times giving Manaus some of the most polluted skies in the world.

Data from the SERVIR Amazon Fire Dashboard indicates that a mixture of fire types burned in the area at the time. Among them: small clearing and agriculture fires that are used to manage crops, deforestation fires ignited to burn trees that were bull dozed and felled earlier during wet season, and grassland fires used to manage pastures. The system also detected large numbers of understory forest fires, a particularly harmful type of fire that can cause damage that persists for decades.

“Deforestation fires are happening this year as well, but I’m especially worried about the addition of so many understory forest fires associated with the drought,” said Douglas Morton, chief of the Biospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “This is a classic response to El Niño. We’ve seen lower rainfall and lower river levels and water tables—conditions that made it more likely that fires could escape their intended boundaries and burn into standing Amazon rainforest.”

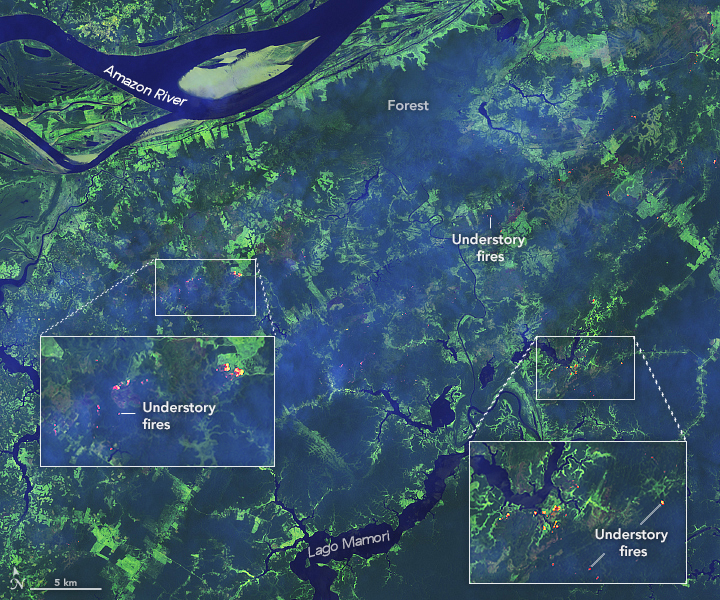

It is possible to identify some understory forest fires with the VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) sensors on the Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 satellites, but it’s challenging for satellites to detect all of them because they often burn beneath dense canopy. Sensors on Landsat 8 and 9 and the Sentinel-2 satellites offer more detailed observations than VIIRS and can sometimes detect understory fires, though they pass over the Amazon basin less frequently than VIIRS.

The false-color image above, captured by the OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager-2) sensor on Landsat 9, shows an example of several understory fires burning in densely forested areas south of Manaus. The use of the sensor’s observations in the shortwave infrared makes it easier to identify fires.

“Understory fires are lose-lose: they degrade the value of forests and contribute to climate change,” added Morton. “We’ve been working as quickly as possible to get data from the SERVIR Amazon Fire Dashboard and several satellites about the location of these fires to fire brigades on the ground to support suppression efforts as quickly as possible. This is an all-hands-on-deck situation.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.

[ad_2]