Extreme weather threatens religious sites

[ad_1]

- Climate change is impacting temples and pilgrimage sites around the globe, wreaking havoc through everything from floods to extreme heat.

- Pilgrims must reckon with the changing climate as they participate in journeys such as Hajj or El Camino de Santiago.

- In some cases, religious practices are place-based, meaning those faiths must adapt if climate change claims their place of worship.

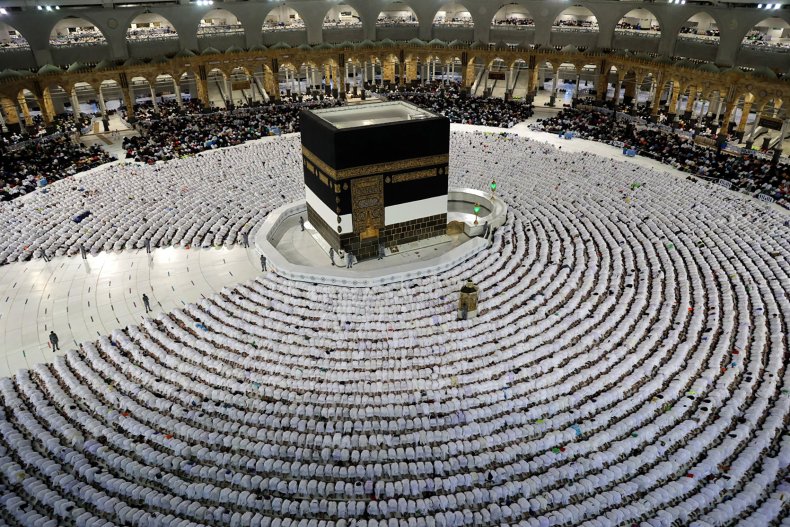

When Ferzaana Sibda, a Muslim from South Africa, traveled more than 6,000 miles to Saudi Arabia for the Muslim pilgrimage known as Hajj, she witnessed people collapse from dehydration. Extreme heat has increased the danger of making the journey, but Sibda doesn’t believe climate change will be the end to Hajj.

“Hajj is the most sacred journey for a Muslim. I don’t believe that anything can deter a Muslim from completing it,” she told Newsweek. “I also feel that the physical struggles experienced builds character and elevates a person’s spirituality and trust in Allah.

“I believe that the effects of climate change will strengthen the believer,” she added.

Floods and extreme heat have destroyed revered religious sites and threatened the lives of people making hallowed pilgrimages. The changing climate has forced people to adjust the way they honor their dead, but for some, there is no easy solution.

Getty

Climate change impact on religion

Subtropical glaciers in high mountainous areas such as the Indian Himalayas are especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change given their low latitudes.

As the glaciers melt, massive amounts of water are trapped in unstable natural dams formed by the glaciers. In 2013, a dam burst and caused devastating flooding in Kedarnath, a town in the Indian Himalayas that is home to the Kedarnath Temple, a famous pilgrimage site that is visited by millions seeking religious blessings each year.

Rushing waters overwhelmed the town after the nearby Mandakini River overflowed. The flood swallowed three-story buildings and killed at least 6,000 people, many of whom were making the pilgrimage.

It’s considered the worst natural disaster to hit Kedarnath and the temple may have been destroyed if a massive boulder hadn’t stopped the floodwaters.

“Every year, there are floods happening now,” Indiana University professor emeritus David Haberman told Newsweek.

Across the globe in Peruvian Andes, glaciers are rapidly disappearing, and taking the healing powers within the ice with them.

Each year, thousands of indigenous worshippers travel to the Sinakara Valley, a glacial basin in Peru, in honor of Qoyllur Rit’i, a four-day religious festival that celebrates the stars.

Getty

Those embarking on the pilgrimage used to be allowed to cut blocks of ice from a glacier in the valley to access its healing powers. The practice was banned in 2004, according to National Geographic, to slow the speed at which the glacier was melting. In recent years, the tropical glaciers in the Andes have decreased by 30 percent, an alarming rate because more than two-thirds of the world’s tropical glaciers are in Peru.

“The glacier is getting smaller and smaller,” Arizona State University associate professor Evan Berry told Newsweek. “The people who organized it had to end the practice of taking ice with you out of respect, but the glacier is significantly smaller.”

Excessive heat caused by climate change has crippling effects in Saudi Arabia, as well, where millions of Muslims—many of them elderly—venture each year to complete Hajj.

Just this year, more than 215,000 Muslims required medical services while completing Hajj, with 4,000 of those transported to the hospital. In years past, the biggest risk of injury was from stampedes, but heat-related illnesses and injuries are on the rise.

Hajj took place from June 26 to July 1, during the season in which Saudi Arabia’s temperatures are the highest. During the pilgrimage, the medical team treated 6,700 cases of heat stress.

Pilgrims are encouraged to avoid direct exposure to the sun when possible and rest well during their journey. In recent years, authorities have implemented measures to counteract the heat, such as using automatic cooling systems to spray pilgrims with water and providing free water bottles and umbrellas. More than 32,000 health care workers enlisted this year to treat those who felt unwell during their journey.

The timing of Hajj changes every year but will continue to occur during Saudi Arabia’s hot summer months until 2026.

I would expect that especially vulnerable people will have real problems with this heat and there [will] even be deaths.

Jos Lelieveld

As temperatures rise from climate change, one expert thinks some Hajj pilgrims will suffer fatal complications.

“I would expect that especially vulnerable people will have real problems with this heat and there [will] even be deaths,” Jos Lelieveld, a professor at the Max Planck Institute for the Advancement of Science, told Time.

Getty

Wildfires cropping up in Europe have had impacts on El Camino de Santiago, the walkable network leading pilgrims to the shrine of the apostle James in the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwestern Spain. The pilgrimage attracts believers and non-believers each year for its transformative experience and can take anywhere from six to 75 days to complete depending on which route a pilgrim takes.

Many of the fires occur in uninhabited areas, but officials must work diligently to extinguish them before they reach the pilgrims, and there are heightened concerns about people’s safety from the smoke.

Warnings of closures along the 1,000-mile journey have cropped up on forums, but considering the mass expanse of the walkable network, it’s unlikely that wildfires will deter pilgrims from traveling at least a portion of El Camino de Santiago.

For some religions, moving important places of worship isn’t an option, even if climate change threatens their existence.

They are connected to some sort of physical space, and if that space is flooded, then you have to adapt.

Rosalyn LaPier

This is particularly true for Native Americans, whose religious practices are often place-based.

“They can’t just pick up and move their church or rebuild it someplace else,” Rosalyn LaPier, a professor at the University of Illinois, told Newsweek. “They are connected to the spring, to the watershed or the mountain or cliff. They are connected to some sort of physical space, and if that space is flooded, then you have to adapt.”

Other faiths encounter various hurdles caused by climate change—everything from floods washing away gravesites to churches receiving higher utility bills.

In 2016, 88 caskets were recovered in two towns in Louisiana after a flood caused the Sabine River to overflow in the spring. The caskets were from five cemeteries, and most of them were buried in surface vaults, in which 75 percent of the grave is underground with the lid above the surface.

Many of Louisiana’s graves are above ground because of the state’s tendency to flood. Frequent floods can disrupt gravesites and the sodden ground makes it difficult to dig fresh plots. However, the floods also can wash away the above-ground vaults, leading to expenses as officials must hunt down the dead and restore them in a new grave.

Other faith-based organizations and places of worship face a simple yet annoying impact from climate change: heightened energy bills.

“There are some individual dramatic examples of how climate change is affecting religious sites and practices, but it’s also really ubiquitous,” Berry told Newsweek. “It’s everywhere. Every church and every house of worship in the world is having to think about the energy bills and take steps to protect those buildings.”

[ad_2]