Mobile clinic has vision of bringing eye care to high-needs schools across Manitoba | CBC News

[ad_1]

It’s only the second week of the academic year, but a mobile clinic that provides eye exams and prescription glasses at Manitoba schools is already visiting its second rural school of the year.

Until now, the Mobile Vision Care Clinic has been so busy serving high-needs Winnipeg schools that it hasn’t been able to expand beyond the city.

“We deal with mostly vulnerable and marginalized [students],” clinic founder and optician Sean Sylvestre said Thursday while visiting Ruth Hooker Elementary School in Selkirk, just north of Winnipeg.

“I’m just passionate about making sure that we remove these barriers and that we ensure that these children have access to care.”

He and his team expect to visit about 100 Manitoba schools this academic year and test approximately 12,000 students. Up to 70 per cent will have some vision problems and a third will need glasses.

For the majority, this will be their first eye exam.

“These are families who maybe don’t have a car, so they’re trying to get to an appointment on the bus or they work three jobs,” said Sylvestre.

“So by us bringing it [the clinic] here, we’re able to test them through the licensed optometrist that works with us. And then if they need glasses, we make sure they get them.”

Eight years ago, Sylvestre was approached by Peter Correia, principal at Mulvey Elementary School in Winnipeg’s downtown. Correia had been taking students for eye exams after school, on his own time, because he saw the need.

Together, they developed a vision for a mobile clinic that could provide eye exams and prescription glasses at schools.

They pitched the idea to the Winnipeg School Division, and the program took off, said Correia.

While it’s been operating since 2017, it’s expanding outside of Winnipeg for the first time this year.

Seeing leads to succeeding

Correia, who has been a principal for two decades, sees the benefits first-hand — improvements not just in literacy, but also in attendance, behaviour and self-esteem.

“When they get their glasses, we see a huge difference in academics … because they’re able to know letter sounds and understand the words,” he said, adding early intervention is crucial.

“And then behaviourally … we know that sometimes students unfortunately do act out because they just don’t want to do the work. They want to kind of divert attention away,” he said.

But with vision issues addressed, “they don’t need to do that because they know that, ‘Yeah, I can do this.'”

Research has found connections between vision problems and poor school performance. While eye tests for children are covered in most provinces, one industry group estimates that 25 per cent of school-age kids have a vision problem but only 14 per cent have had an eye exam by the age of six.

The Manitoba mobile clinic’s optometrist receives fees for exams only, not from the sale of glasses. The clinic provides glasses at 65 per cent off, but for families who don’t have insurance and can’t afford to buy them, the clinic donates them with the support of an international eyeglass foundation.

Sylvestre has a long wait list of rural and First Nations schools to visit. He would love to expand but needs more optometrists interested in joining his team.

‘If you can’t see, you should probably get glasses’

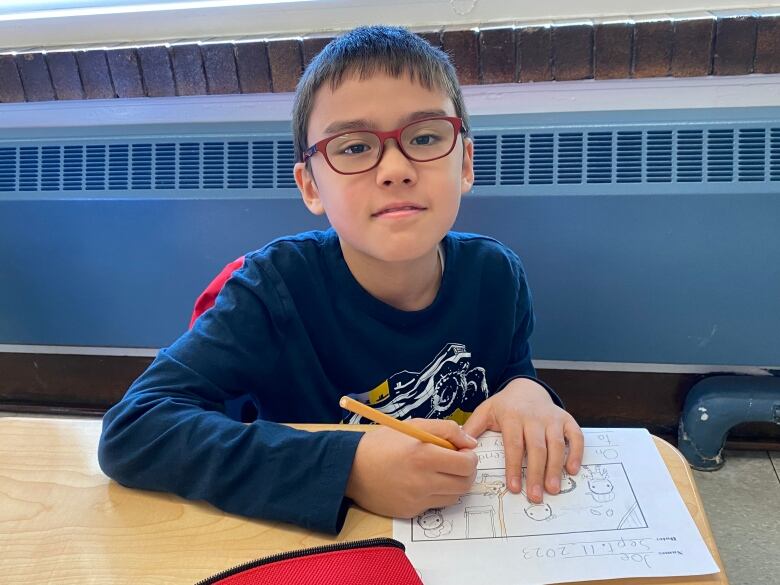

Mulvey School student Joe Reader, 8, says he loves reading “big” books like encyclopedias. He got glasses after a school eye exam two years ago.

“I see stuff that isn’t there when I take them off, and it looks a little blurry too. When I wear my glasses, it doesn’t,” he said.

His mother, Kaori Matuo, said she is grateful the mobile vision clinic caught his problem early.

“We asked him [if] he can see or not and he would say, ‘Yes, yes,'” she said.

“So we thought he didn’t have problems, and then he got his eyes tested at school and he got glasses, and we were surprised.”

Classmate Betel Kelem, 8, also got her glasses after an eye exam by the mobile clinic.

“I picked glasses out and these were perfect for me,” she said. “If you can’t see, you should probably get glasses.”

Back at Ruth Hooker School, seven-year-old Elsa Eleazu found out she needs glasses after her test.

“When it’s far away, I can’t [see]. When it’s close, I can,” she said.

She tried on several pairs but chose a blue pair because her favourite Disney princess — who shares her name — wears a blue dress.

‘Something very magic’

Principal Kristine Duke watched the excited students go through the testing stations, saying she’s grateful the mobile clinic is getting outside of Winnipeg and into rural schools like hers.

“We have a high Indigenous population here — 70 to 80 per cent declared — and we also have newcomer families,” she said.

“So we have families that maybe don’t readily have access to eye doctors, family doctors, the funding for things like that, so this is critical.”

Sylvestre, who has been recognized nationally and provincially for the mobile clinic program, said he was moved by the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action. He sees this work as his contribution.

“We fundamentally believe that vision care and proper vision is a fundamental right for all Canadians,” he said.

As well, “there’s something special about working with students who don’t know that they can’t see and seeing the difference in their lives,” he said.

“When you help change that … there’s just something very magic about that.”

[ad_2]