Patt Morrison: How California got its good name — a 1500s novel and scores of fascinating people

[ad_1]

People say — and by “people,” I mean me — that there are two kinds of Californians: the ones who were lucky enough to be born here, and the ones who are smart enough to move here.

And by Californians, I mean all of the humans who have ever made a home of this place.

For this momentary historical purpose, though, we mark the birthday of California as a state: that fast-tracked date of Sept. 9, 1850, when California, with all its gold and gorgeousness, joined the union as its 31st state. President Millard Fillmore — no jokes please — made it official with his signature, although word of it didn’t reach California until Oct. 18.

It took classic episodes of political horse-trading and back-slapping to happen, and it delivered a lot of back-stabbing to earlier original Californians, like Native Americans and Mexican Californios.

Admission Day was a state holiday until 1984, when Gov. George Deukmejian un-decreed it, so take this opportunity to celebrate in your own fashion.

California is not the biggest state by acreage — Alaska takes that blue ribbon, with Texas as runner-up — but we are the most populous and arguably the richest.

Newsletter

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there’s someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And home to more Nobel laureates and billionaires and sheer geniuses — and any number of eccentrics, which may be a substantial overlap — in any kind of undertaking than any other state.

Naturally, we have a pantheon. Nearly 20 years ago, the then-first lady, Maria Shriver, worked with the California Museum to inaugurate an exhibit of remarkable women, and from that she and Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger developed the state’s Hall of Fame, with a new and select “class” of honorees every year.

Who qualifies? Those who’ve lived in California for at least five years and transcended their own fields to make “a lasting, significant contribution to the state, nation and world,” people who embody “the spirit of California and the California Dream,” and whose life stories and work can “motivate and inspire people to further their own dreams through their unique story and accomplishments.”

There are nearly 40 million Californians breathing right now, and millions of others who are dead but not necessarily gone from our mindscape; there are fewer than 200 Californians, living and dead, in the Hall of Fame, so the process is necessarily picky.

Shriver is in it, but her ex-spouse and our ex-governor, Schwarzenegger, is not. President Reagan, a Californian smart enough to move here, is in, but President Nixon, a Californian lucky enough to be born here, is not. I’ve always thought that by disposition, Reagan, the relentless optimist, was more essentially Californian than Nixon, the pessimist with a pinstriped spirit.

But for Admission Day, I’d like to spend some time on the ones you don’t find there — and maybe should.

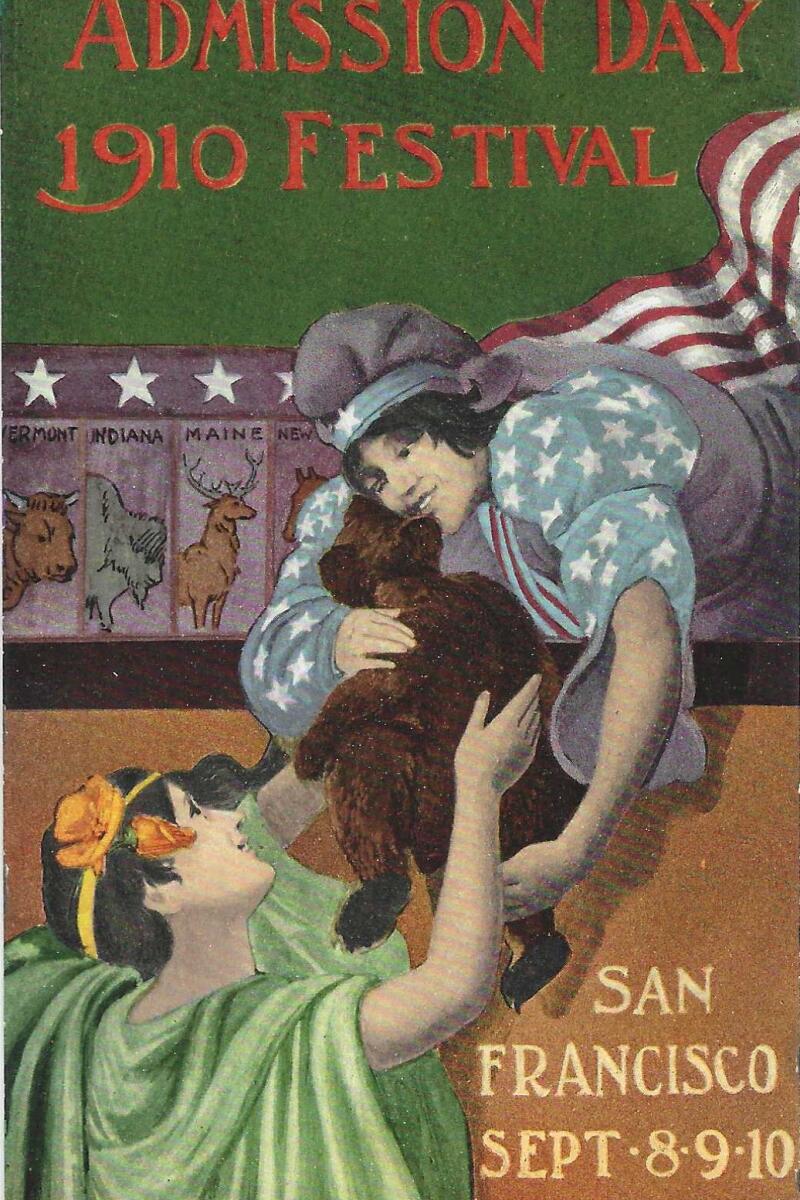

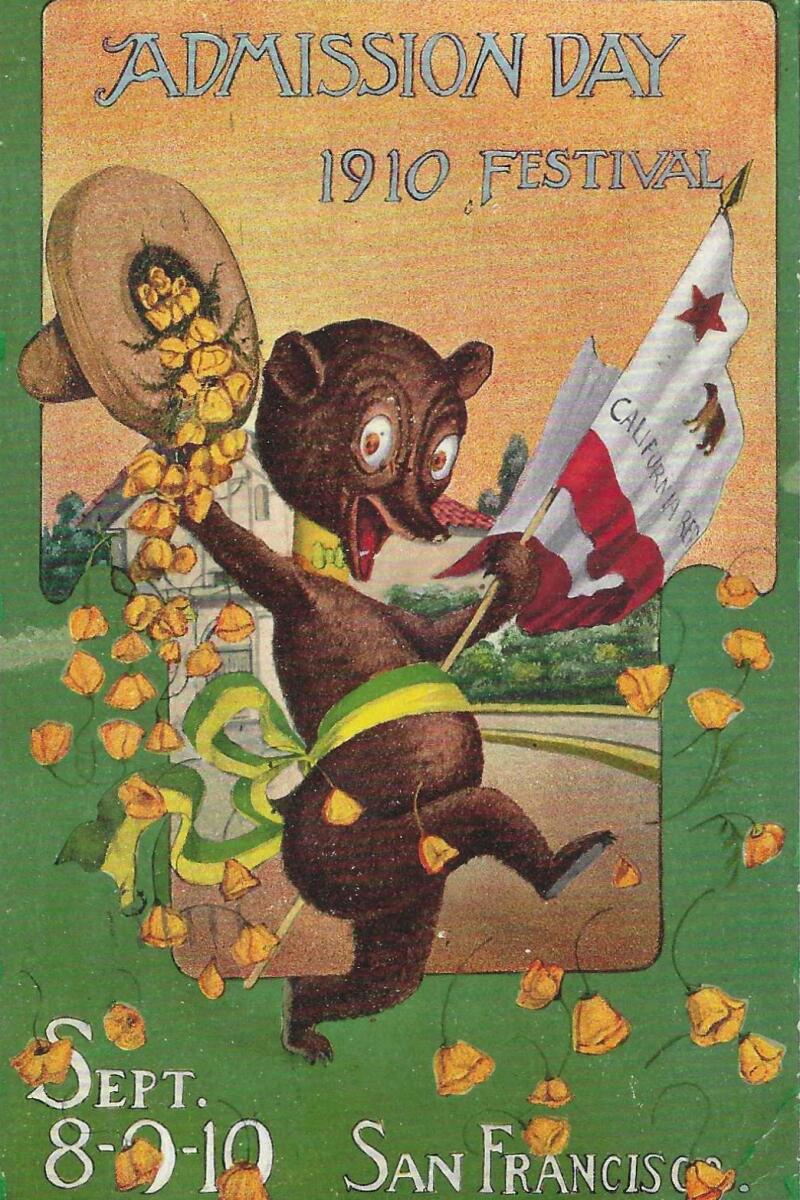

Vintage postcards, from Patt Morrison’s collection, commemorate California’s 1910 Admission Day festival.

Obviously, there are some wobblers. Joe DiMaggio was born in San Francisco and played in the Pacific Coast League but probably struck out by spending his entire major league career as a New York Yankee. I understand. Ditto Robert Frost, who was born in San Francisco but decamped for his soul’s latitude in New England before he was 10.

But where is Biddy Mason? This extraordinary Black woman, a nurse and midwife, was still enslaved when she and others were brought to the free state of California by a Mormon settler from Mississippi in 1851. When it looked like the settler was about to skulk off for Texas with his human property, a Los Angeles judge was asked to decide the status of the Black people. This was at a moment when Black people could not testify in court, not even in the “free” state of California. In January 1856, a Los Angeles judge ruled that Biddy, her family and her companions “are entitled to their freedom, and are free and cannot be held in slavery or involuntary servitude.” Biddy Mason became a foundational figure in L.A. — a real estate mogul, probably the richest Black woman west of the Mississippi, a founder of the First African Methodist church here, and a legendary philanthropist. The mayor — the white mayor — spoke at her memorial.

What about Isadora Duncan? The legendary founder of modern dance was born in Oakland, invented her art there, and taught dancing to children when she was a child herself, before moving to Chicago at about 18. “My life and myself were born under the sea,” she wrote, under the augury of “the star of Aphrodite.” Every step, every movement of modern dance owes a debt to Isadora Duncan, Californian.

And what about that other daughter of Oakland, Gertrude Stein? The woman who mothered the style-shattering artists of Paris in the 1920s and created her own artfully fractured prose spent her childhood and most of her teen years in an Oakland of “joyous sweating, of rain and wind, of hunting, of cows and dogs and horses … of lying in a hollow all warm with the sun shining while the wind was howling.”

She returned to Oakland many years later and made her much-mangled observation. “What was the use of my having come from Oakland it was not natural to have come from there yes write about it if I like or anything if I like but not there, there is no there there.” Isn’t that the Californian’s perpetual lament, that nothing ever is, nothing stays the way it was?

And Jack London? This San Francisco working-class boy was taken under the wing of a librarian named Ina Coolbrith — who became the state’s first poet laureate. London did his homework and research in an Oakland waterfront salon that’s still in business. His writing took readers to the last remote spots of an increasingly civilized world, and into the misery and poverty of that supposedly civilized world. His ardor for the natural world and the creatures in it still reaches and touches his readers.

I’d argue for scientists Walter and Luis Alvarez, son and father. You want global influence? Michael Crichton, Steven Spielberg, and every dinosaur-mad 8-year-old in the world know the Alvarezes’ work, if not their names. Alvarez pere won a Nobel Prize for his discoveries in particle physics, but it was Alvarez fils, working with his dad, who came up with the well-accepted conclusion that a massive asteroid smacked into the Earth about 65 million years ago and wiped out virtually all the dinosaurs and cleared the Earth for the likes of us.

It’s more than shameful that Thomas Starr King is not already in this Hall of Fame. Abraham Lincoln credited him with helping to keep California from bailing out of the Union and going independent during the Civil War. The ardor and the energy the little minister spent campaigning up and down the state, speaking persuasively to crowds of thousands, cost him his life and health; he died at the age of 39. Until 2006, his statue was one of two of eminent Californians to stand in Statuary Hall at the U.S. Capitol. It got bumped to be replaced by Ronald Reagan’s.

And where is Ralph Bunche? It always surprises me that Bunche is an afterthought — the first African American; the first Black person, period — to win a Nobel Prize, and an early leader in civil rights. He grew up here, was valedictorian at Jefferson High School and a Phi Beta Kappa political science student at UCLA. He took on critical posts in the State Department and at the United Nations, and in 1950 — 14 years before Martin Luther King Jr. won his peace prize — Bunche was awarded the honor for negotiating the 1949 Middle East accord ending the Arab-Israeli war and drawing new territory lines in the region.

And there must be a place for Toypurina. This 18th century Native American woman has been interpreted and reinterpreted, as women often are, through the lens of the historians and stakeholders. She was a member of the local Kizh tribe and was credited with magical and healing powers. Perhaps that’s one reason she helped to organize and lead an uprising in 1785 against the San Gabriel Mission. Her impassioned statement at her trial may have been cobbled together after the fact, but the sentiment rings true: “I hate the padres and all of you, for living here on my native soil, for trespassing upon the land of my forefathers, and despoiling our tribal domains.” She was exiled to a distant mission and married to a Spanish soldier.

Here is where you can nominate a deserving Californian of your own.

There is one man who fails at least one of the criteria; he never lived in California, because the actual California was unknown to his world. To Castilian author Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo goes the credit for being the first to put “California” on the printed page, in 1510, in his novel “Las Sergas de Esplandian.” In chapter 157, he described the place as an island “very close to the coast of Earthly Paradise, which was populated by black women without a single man among them, who were almost like the Amazons in their style of life. They had beautiful and robust bodies, striving and ardent hearts, and were very strong,” and were ruled by a queen named Calafia.

Ninety-five years later, the novelist Miguel de Cervantes put this adventure novel on the imagined bookshelf of his gallant picaresque dreamer, Don Quixote de la Mancha — a true Californian if ever there was one.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

[ad_2]