Uncontrolled chemical reactions fuel crises at L.A. County’s two largest landfills

[ad_1]

Hundreds of feet underground, in a long-dormant portion of Chiquita Canyon landfill, tons of garbage have been smoldering for months due to an enigmatic chemical reaction.

Although operators of the Castaic landfill say there’s no full-blown fire, temperatures within the dump have climbed to more than 200 degrees, and area residents have complained of a burned garbage odor wafting through the neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, 12 miles to the southeast, Sunshine Canyon landfill has suffered water intrusion from torrential storms earlier this year. That seepage has fueled bacteria growth within the Sylmar landfill, giving rise to putrid odors that have nauseated students and staff at a local elementary school.

The highly unusual reactions at Los Angeles County’s two largest landfills have raised serious questions about the region’s long-standing approach to waste disposal and its aging dumps. These incidents have impaired pollution control systems, allowing toxic gases and polluted water to migrate into unwanted areas.

They have also triggered thousands of odor complaints, dozens of environmental penalties and renewed calls to shutter the landfills.

Both facilities remain operational and each continues to accept more than 7,000 tons of trash a day. However, many residents who live nearby fear the potential of even greater problems and say that government officials and landfill operators need to take the problems more seriously.

Trucks haul dirt that is used to cover the Sunshine Canyon landfill.

“If temperatures get to a certain point, there isn’t going to be much that can be done,” said Sarah Olaguez, a Val Verde resident whose family lives less than a mile from Chiquita Canyon. “I feel like we’re on the precipice right now. It’s a train wreck waiting to happen. It’s scary and I feel trapped.”

The scorching temperatures within Chiquita Canyon Landfill have caused pressure to build inside the 639-acre facility and forced contaminated water to burst onto the surface.

Analyses by CalRecycle, the state agency that oversees solid waste and recycling facilities, described the situation as a “heating/ smoldering” event that has expanded in all directions since the summer. By November, the reaction area had grown by 30 to 35 acres, according to the agency.

Already, the heat has melted or deformed the landfill’s gas collection system, which consists mostly of polyvinyl chloride well casings. The damage has hindered the facility’s efforts to collect toxic pollutants.

“When there are high temperatures in the landfill gas, that can melt or deform some of the landfill gas collection system components,” said Angela Shibata, senior air quality engineering manager with the South Coast Air Quality Management District. “You can imagine when you have very hot temperatures and you have plastic materials as conveyance mechanisms for extracting and vacuuming out that gas, that can cause all kinds of issues.”

Abnormally pungent odors began drifting into neighboring communities last spring and intensified over the summer. In Val Verde, an unincorporated community of around 3,000 residents, some say they have suffered headaches, dizzy spells and difficulty breathing.

“The odors were so bad that my wife and I were getting sick inside our house — with the doors and windows closed,” said Steven Howse, a longtime Val Verde resident. “My kids can’t go outside, and my son loves to go and jump on the trampoline or ride his bike. But he’ll come in saying, ‘Oh, my stomach hurts, Dad. I don’t feel good.’”

1

2

3

1. Sarah and Christian Olaguez live with their children in Val Verde, where they have endured the smell from the Chiquita Canyon Landfill. When the couple bought their home in 2017, the were told the landfill would close in 2019. Now, it might not close until 2037 and they are desperate. “I’ve told my husband, we’ll sell the house and live in a trailer if we have to,” Sarah Olaguez says. 2. For leaving the house, a mask with odor-reducing filters hangs near the Olaguezes’ front door. 3. An odor reducing air cleaner, right, also runs inside the home.

According to the South Coast Air Quality Management District, the odors are the result of a rare chemical reaction in a closed portion of the landfill that no longer receives trash.

The reaction may have started when oxygen entered the well system, which is designed to pump out landfill gases like methane.

“Think about if you’ve ever lit a campfire and then tried to blow on it to get it going,” said Morton Barlaz, professor of civil engineering at North Carolina State University. “When you blow on it, you get more flame.”

The landfill recorded elevated oxygen levels in hundreds of its gas wells over the past two years, according to CalRecycle. As temperatures rose to near-boiling heights this year, carbon monoxide levels climbed to more than 1,000 parts per million, which CalRecycle considers positive indication of an active underground landfill fire.

CalRecyle declined to comment further on its report. Chiquita Canyon’s website, however, claims there is no subsurface fire.

Waste Connections, the landfill operator, is trying to slow and eventually stop the reaction by removing excess gases and liquid, according to Steve Cassulo, Chiquita Canyon’s district manager.

Work crews have drilled new gas wells and fitted them with steel pipes that can survive the heat. They’ve installed a new flare to burn off flammable landfill gases.

“Chiquita, along with its various regulatory oversight agencies, has been working cooperatively to rapidly address these issues,” Cassulo said in a statement. “Chiquita takes very seriously its role in the safe operation of the landfill.”

Still, county officials say the problem could persist for months.

As residents have stayed indoors more and run their air conditioners to filter out smells, L.A. County Supervisor Kathryn Barger has tried to offer relief by setting aside funds to help with their electric bills. Around 900 households surrounding the landfill are eligible.

“The good news is, this is only happening at Chiquita,” Barger said. “The bad news is we’ve never seen anything like this, and if we don’t understand what triggered it, it could happen at other landfills that are dormant. So it’s important for us to get a handle on it.”

Tons of buried garbage have been smoldering for months in a long-dormant portion of Chiquita Canyon landfill.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

The situation has been a nightmare for Olaguez, who lives in Val Verde with her husband, Christian, and three children.

The couple bought their home in 2017, attracted to the mountain views, tranquility and small-town life.

At the time, they were told the landfill was nearing its capacity and was poised to close when it reached 23 million tons of waste, or by November 2019.

Instead, Los Angeles County granted the operator permission to expand and continue operations until it reaches a capacity of 60 million tons, or by 2037.

“I’ve told my husband, we’ll sell the house and live in a trailer if we have to. We’ll probably lose money, but at least won’t have to deal with this.” Olaguez said.

Meanwhile, in the northern San Fernando Valley, problems at Sunshine Canyon Landfill appear to be the result of extreme weather conditions.

Protesters have complained for decades about noxious odors, diesel truck traffic and dust emanating from the 1,036-acre dump. Over the last year, however, odor complaints have increased drastically and are believed to be the result of heavy rains last fall and winter.

Between October 2022 and March 2023, Sunshine Canyon recorded more than 55 inches of rain, almost four times the amount the site typically sees in a year. Then in August the site was hit by tropical storm Hilary, which brought an additional 5½ inches.

Officials say this precipitation filtered into the landfill, drenched decomposing garbage and created an ideal environment for the breeding of bacteria that release methane and smelly hydrogen sulfide.

The downpours also eroded portions of the landfill’s soil cover, leaving garbage exposed and strewn offsite, exacerbating the odor issues.

The air quality district has previously required the landfill to install pumps to remove rainfall and allow the gas collection system to continue to operate, according to Nicholas Sanchez, assistant chief deputy counsel.

“But what we’ve seen with these extreme weather events is so much liquid gets into the well that it completely inundates the system and then the pumps no longer function,” he said.

Sour trash odors have plagued Van Gogh Charter School, which serves about 400 students, about a mile from the landfill. The Los Angeles Unified School District allowed an air monitor to be built on school grounds and encouraged staff to report odor issues to the air district, which automatically constitutes a violation.

This year, Browning-Ferris Industries of California, the landfill operator, has been the subject of 1,500 odor complaints and around 60 air district violations.

Granada Hills resident Erick Fefferman lives near the Sunshine Canyon landfill. He says odor and dust from the landfill are constant problems for the neighborhood.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

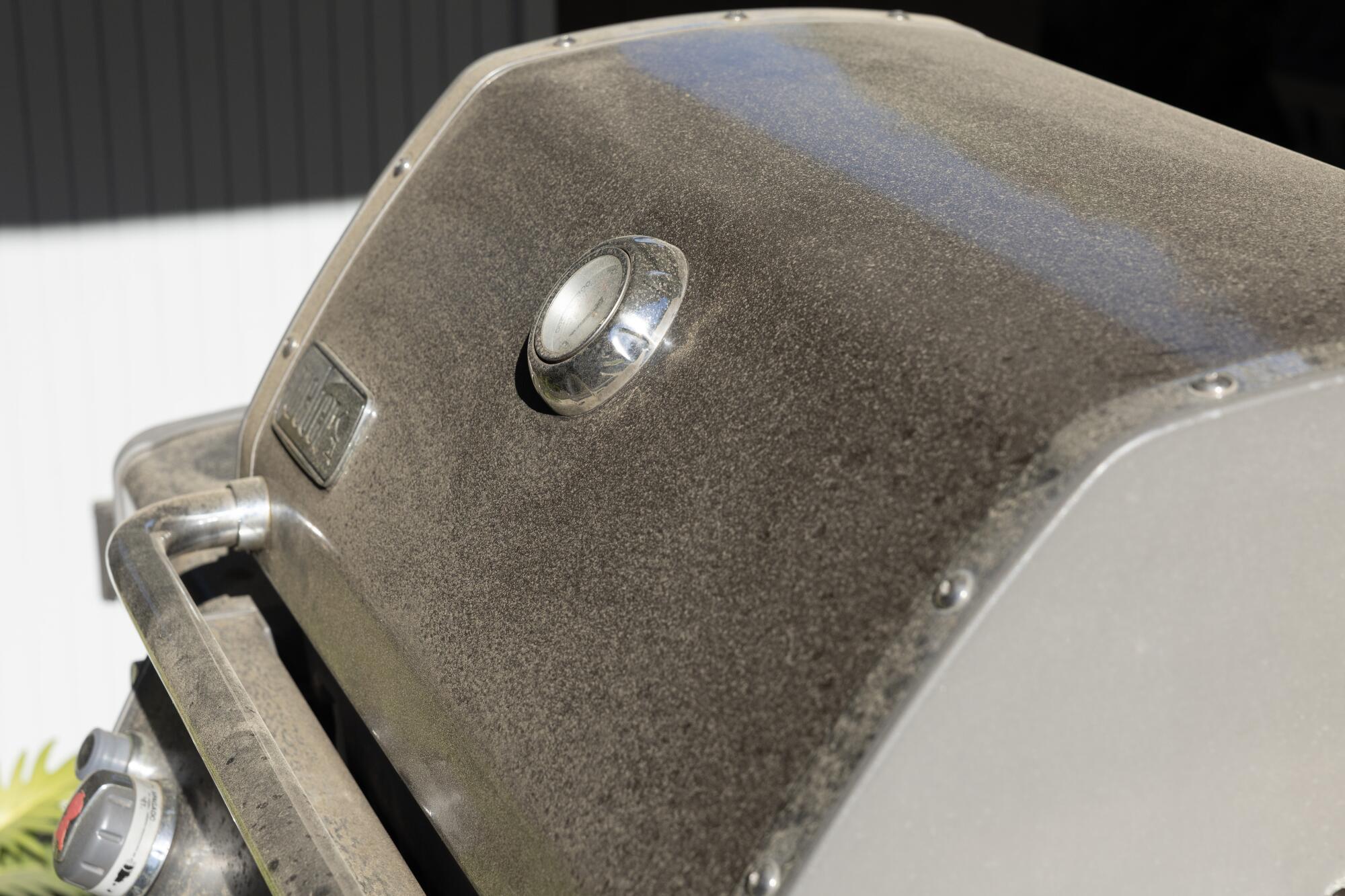

A layer of dust coats an outdoor barbecue in Granada Hills. Residents complain of odor and dust from the nearby Sunshine Canyon landfill.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Granada Hills resident Erick Fefferman, whose 6-year-old son attends Van Gogh, said the school has canceled recess at least once this year in response to putrid smells and at times has refrained from having students line up outside the building in the morning.

Fefferman, who used to walk his son to school, said the odors have deeply distressed his son.

“He had like a nightmare recently where he woke up crying because he said, ‘I had a nightmare that we lost our house and we have to live at the landfill,’” Fefferman said about his son. “It’s such a common occurrence. Even at only 6 years old, he knows that there’s this thing happening in proximity to his home and his school.

“That’s like the boogeyman to him, this landfill.”

The smells have also drifted to their neighborhood, a collection of Midcentury Modern homes at the base of the Santa Susana Mountains. Earlier in the year, when the stench was at its worst, Fefferman, who has asthma, said he had to use his inhaler every day.

In an effort to suppress odors, the landfill trucks in tons of soil to cover the mounds of garbage it receives. But Fefferman said this dirt sometimes blows onto his home, coating his solar panels and sullying his pool and koi pond.

The landfill operator has installed a new system that it says will handle more rainfall and better divert the water to allow operations to continue despite rainstorms.

“Without question, there have been ongoing challenges from Hurricane Hilary,” said Jeremy Walters, a spokesperson for the landfill. “Excessive rain events like that can have lingering impacts, sometimes for weeks or months, on incoming wastes. In addition, seasonal wind patterns historically shift this time of year, which, combined with excessively wet wastes, can make the operating environment at the site quite dynamic.”

However, some residents say part of the problem is the landfill was never properly sited.

It began as an illegal dumping ground in the mid-1950s, when people discarded trash in the canyon without permits. In 1958, the city of Los Angeles permitted a 40-acre landfill, which later expanded into the county’s largest dump site.

Due to its location, winds bluster through the Newhall mountain pass and disperse the odors onto Granada Hills and Sylmar.

Wayde Hunter, president of the North Valley Coalition of Concerned Citizens, has been raising objections to these nuisances for decades. It’s hard to get elected officials to pay attention, he said.

“We’re being buried in trash up here and we’re not getting any relief,” Hunter said. “We certainly don’t deserve to have this landfill in the place where it just impacts daily life.”

Experts say that organic waste is at the root of the situation at Sunshine Canyon and Chiquita Canyon landfills.

Bacteria feed on food scraps, yard trimmings and paper products. In the process, they produce methane, a greenhouse gas that’s at least 80 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide over 20 years.

In 2016, then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law calling for the reduction of organic waste in California landfills by 50% by 2020 and 75% by 2025.

Between 2014 and 2021, the state has cut its annual tonnage of organic waste from 21 million to 19 million, a 10% reduction, according to CalRecycle.

But the agency noted the 2016 law only went into effect last year, including its requirement for every jurisdiction to provide organic waste collection services to all residents and businesses.

Mike Mohajer, a retired engineer with the L.A. County Department of Public Works, said the lack of substantial progress toward achieving these goals is due, in part, to inadequate state funding and limited infrastructure in place to divert such a vast amount of waste.

“Over the past 20 years, we have been arguing over ways to manage organic waste other than incineration,” said Mohajer, who now serves on an L.A. County waste management task force. “You can use a portion of the organic waste as a compost. But we do not have the market to turn 11 million tons of waste into compost.”

As policymakers wrestle with this dilemma, residents who live near the two landfills have asked sanitation agencies to explore diverting some tonnage elsewhere.

This includes a long-idled plan to transport Los Angeles’ trash via railcar and bury it in a remote desert landfill more than 100 miles east of San Diego.

Representatives for the L.A. County Department of Public Works acknowledged there is capacity at other landfills. But there could be unintended consequences as a result, such as higher costs or more greenhouse gas emissions from trucking it a longer distance.

Granada Hills residents living nearby complain of dust and odors from Sunshine Canyon landfill.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

Fefferman said he doesn’t want to shift the burden to another community. But at the same time, he and his neighbors shouldn’t shoulder the burden for the entire county, he said.

“We understand that we also put our black trash cans out on the curb once a week as well. So we’re not saying, ‘Not in my backyard.’”

The problem, he said, is Sunshine Canyon and Chiquita Canyon each accept more than 2 million tons of garbage a year — 70% of the county’s solid waste.

“That seems like it’s more than our fair share,” he said.

[ad_2]