Netflix film ‘The Saint of Second Chances’ looks back at Mike Veeck’s highs and lows

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24920023/The_Saint_of_Second_Chances_00_02_44_03.png)

[ad_1]

In the closing credits of the heartwarming and wickedly funny and creatively rendered Netflix documentary ‘‘The Saint of Second Chances,’’ which premieres Tuesday, you’ll find this beauty:

ANDY THE CLOWN . . . DAVID LOWE

That’s right: In one of the dramatic re-creations in this nonfiction biopic of Mike Veeck, the baseball promo guru extraordinaire and son of the legendary Bill Veeck, they’ve got a guy playing the late and beloved Andrew Rozdilsky Jr., a k a Andy the Clown, who for three decades roamed the stands at Old Comiskey Park in his trademark red bowler hat, whiteface and polka-dot get-up. He’s on-screen for all of about seven seconds, but talk about a White Sox deep dive!

‘The Saint of Second Chances’

Any telling of the tale of Mike Veeck is to going to devote a substantial portion to his tenure working for his father, Bill, in the 1970s, which means we’re going to revisit Disco Demolition and its complicated history. In the hands of talented co-directors Morgan Neville (Oscar winner for ‘‘20 Feet From Stardom’’) and Jeff Malmberg (‘‘Marwencol’’), what makes ‘‘The Saint of Second Chances’’ extra-special and memorable is the story of what happened to Mike Veeck after his career imploded in the wake of all those disco records exploding and how he found redemption in the only things that truly seem to matter to the man: family and baseball.

Mike Veeck is pictured with father Bill in a photo from “The Saint of Second Chances.”

Whether you’re a diehard baseball fan (and, in particular, a White Sox fan) who recognizes everything from the aforementioned Andy the Clown to the welcome appearance of slugger Lamar Johnson to the references to the Bard’s Room to a poignant interview with Darryl Strawberry or just a casual baseball observer, ‘‘The Saint of Second Chances’’ has a universal appeal in its core story. Mike Veeck is a compelling, charismatic, complicated character who fills a room with his boisterous laugh and is admirably frank in talking about the extended period in which he hit rock bottom and crawled inside of a bottle, to the point where a neighbor referred to him as ‘‘the loneliest man in the world.’’ Mostly, though, it’s about the family and the sport that gave him that proverbial second chance.

With the great Jeff Daniels providing honey-coated narration, ‘‘The Saint of Second Chances’’ relies on a treasure trove of archival footage and photos but also employs some bold strokes to tell the story. In dramatic re-creations, Mike Veeck plays his father, Bill, while actor Charlie Day (‘‘It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia’’) plays Mike — and plays him quite well. We learn that while Bill Veeck was carving out a unique place in baseball history and driving traditional owners nuts, he had little time for his son. So when Bill offered the 20-something Mike a job with the Sox and the chance to spend quality time together, Mike jumped at the opportunity. (In one terrific scene, we see Mike hustling to restock the scoreboard with fireworks as the 1977 White Sox set a team record for home runs.)

Then came Steve Dahl’s Disco Demolition, which was conceived as just another promotion — the flip side of a successful ‘‘Salute to Disco’’ at Comiskey Park. At the outset of the scheduled doubleheader on July 12, 1979, with some 50,000 fans filling the park and thousands more gathered outside, Harry Caray exclaimed: ‘‘This has got to be the youngest crowd ever to fill up Comiskey Park. Just a tremendous promotion.’’

Until it wasn’t.

Fans at Comiskey Park rush the field during Disco Demolition, an ill-fated 1979 White Sox promotion conceived by Mike Veeck.

We all know what happened next. The jarring explosion of thousands of disco records in center field. Fans swarming the field, ripping up the bases and running wild. The Sox having to forfeit Game 2. (For the record: The teenage me was in the right-field upper deck with a couple of buddies. It never occurred to us to storm the field. We thought that was nutso.) Though it wasn’t intended as such, Disco Demolition came to be viewed by many as an attack against Black music and against the gay fan base who embraced disco.

‘‘What was supposed to be a night of fun unintentionally hurt a lot of people,’’ narrator Daniels says. Mike Veeck adds: ‘‘Looking back now, through that lens, I realize that not only is it complicated, but more importantly, it’s painful to people. It was never intended to hurt any group. . . . If I could go back, I wouldn’t have done it.’’

With a title card telling us, ‘‘Several S—– Years Later,’’ we race through a montage of Mike Veeck getting hammered on drink and drugs, having a heart attack, getting married, having a son and naming that son Night Train Veeck and, on the verge of disappearing into the void forever, finding new life as the owner of the independent league St. Paul Saints in 1993.

Veeck ushered in a whole new era of wacky promotions, whether it was having a 17-inch ‘‘mini-tron’’ TV in the outfield or a pig mascot bringing baseballs to the plate umpire or onetime co-owner Bill Murray hawking programs. He also brought in Ila Borders to be the first female pitcher since women in the Negro Leagues to start a men’s professional baseball game and signed Strawberry in 1996 at a time when Major League Baseball considered Strawberry toxic. (‘‘St. Paul brought me back to life,’’ Strawberry notes.)

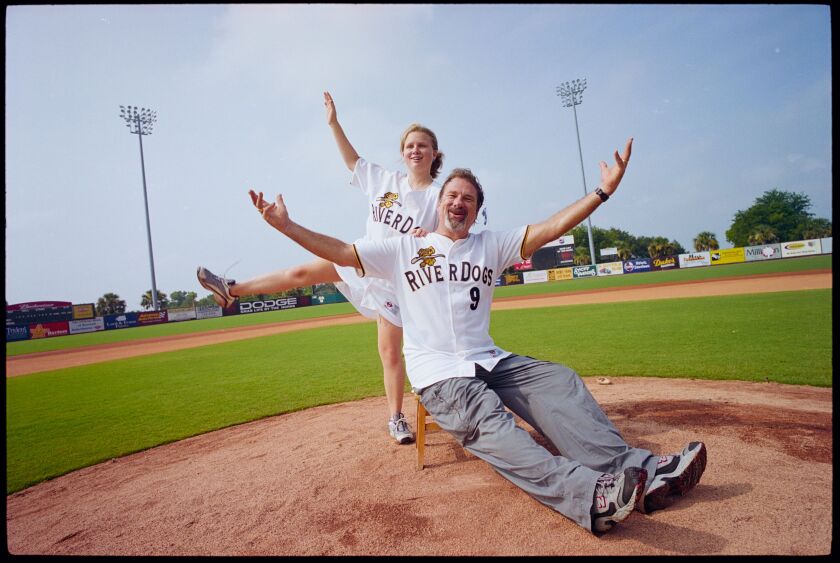

“The Saint of Second Chances” takes a dramatic turn in recounting Mike Veeck’s time with daughter Rebecca, who had Batten Disease.

In the late innings, ‘‘The Saint of Second Chances’’ takes a dramatic turn, as Mike and Libby Veeck’s daughter, Rebecca, who loved baseball and being at the ballpark since she was a little girl, is diagnosed with Batten disease, a group of fatal genetic disorders. Before Rebecca completely loses her eyesight, Mike and Libby take her to 30 states and five countries.

Rebecca was just 27 when she passed away. You can see the pain will never leave Mike Veeck, but you also come away with the sense he’s grateful for finding his stride and his Second Act in time to be there, to be present, to be a father to his daughter.

[ad_2]