Is that snack chocolate or ‘chocolatey’? How skimpflation might be affecting your groceries | CBC News

[ad_1]

Daniel Noël of Sherbrooke, Que., stopped snacking on Quaker Dipps granola bars last year after he took a bite and noticed something was up.

The bar tasted “very old,” Noël, 51, told CBC News in an email. “I first thought that the product was way over its expiration date.”

It wasn’t. So Noël compared the ingredient list on the bar’s box with older packaging and made a discovery: the Dipps bars’ previous milk chocolate coating, made with cocoa butter, had been replaced with a “chocolatey coating” made with a typically cheaper fat — palm oil.

“I feel that I’ve been fooled,” said Noël. “It’s not the same product. It’s not the same taste.”

You’ve probably heard about shrinkflation: when manufacturers shrink a product, but not its price.

But you may be less acquainted with skimpflation: when companies swap out ingredients in food products for cheaper ones — also without lowering the price.

“It’s really an unknown, sneaky way to give you less for your money,” said Boston-based consumer watchdog Edgar Dworsky, who tracks both skimpflation and shrinkflation.

He believes the recent spike in inflation has sparked a rise in skimpflation, as companies grapple with rising supply costs.

But it’s difficult to gauge the extent of the practice, because it’s hard to detect.

“We don’t know the recipe,” said Dworsky. “So it’s very easy to pull the wool over our eyes.”

No more milk chocolate?

Quaker’s owner, U.S.-based PepsiCo, did not respond to requests for comment about the switch to the “chocolatey coating” made with palm oil.

According to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, products must meet certain criteria to be labelled “chocolate”, including a specified minimum amount of cocoa butter and powder, and no vegetable oils.

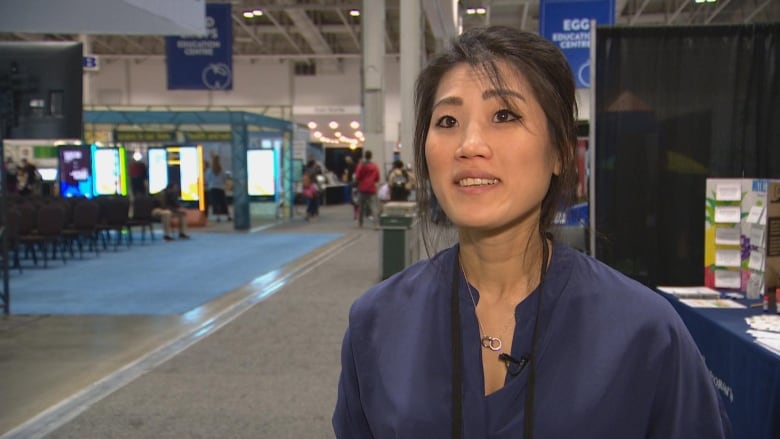

“It appears that [Quaker has] replaced the milk chocolate ingredient to something that doesn’t meet the standard of identity for Canada. So now they’re calling it ‘chocolatey coating,'” said Jennifer Lee, a registered dietitian and doctoral candidate in nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto.

Noël said he didn’t notice the recipe change when he bought the Dipps bars, as the older and current packaging look very similar. The current box, however, no longer boasts that the bars are “made with real milk chocolate.”

“I suppose that most people won’t notice,” said Noël. “That’s where the company wins.”

When companies revise recipes in Canada, they must update the ingredient list on product labels, but they don’t have to make any other efforts to alert customers.

Lee says the federal government should also require companies to redesign packaging when they revamp recipes, so shoppers understand the product has changed.

“I think it comes down to clearly communicating to consumers so that they can make informed decisions,” she said.

Less oil, more salt

Last month, the federal government announced plans to investigate skimpflation, stating the practice hurts Canadians. But Ottawa has no action plan as of yet.

To help alert shoppers to recipe changes, consumer advocate Dworsky posts on his website what he believes are examples of skimpflation.

They include Wish-Bone House Italian salad dressing, which is sold in the U.S. and on Amazon’s Canadian shopping site.

After comparing the nutritional details on an older and current version of the dressing in August, Dworsky concluded that the brand reduced the oil content by more than 22 per cent and appears to have made up for it with added water and sodium.

“Water is cheaper than oil,” he said. “And if you can make consumers believe they have what appears to be the same product, but it costs you less to make, that makes [companies] more money.”

But some customers noticed the change. Dozens have complained about the new recipe on Wish-Bone’s website, with comments such as “tastes horrible!” and “who wants a watered down bland salad dressing?”

U.S.-based Conagra Brands, which makes the salad dressing, did not reply to requests for comment.

Featured VideoConsumers and advocates are calling for more transparency around the practice of shrinking packaging rather than increasing prices, known as ‘shrinkflation.’ Other countries make companies display weight changes on product labels.

What can customers do?

Nutrition expert Vasanti Malik said recipes change regularly in the food industry for a variety of reasons, including supply chain problems and customer preferences. So, she argues, it would be impractical and potentially cost-prohibitive for manufacturers to alert customers on the packaging every time there’s a recipe revision.

“It’s just not a feasible strategy,” said Malik, an assistant professor teaching nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto. “It comes down to the individual to really navigate those food ingredient lists.”

But dietitian Lee argues that companies flagging recipe changes could actually be good for business.

“The better you communicate these changes to consumers, the better we can build trust between manufacturers and consumers,” she said.

If shoppers do notice a negative change in a food product, Dworsky recommends they complain to the manufacturer.

That’s what many customers did when, last year, Conagra reduced the oil content in its Smart Balance buttery spread — sold in the U.S. — by 39 per cent. Dworsky believes it was a cost-cutting move.

In response to the change, customers flooded the brand’s website with negative reviews. The criticism appears to have had an impact — the brand now says it’s switching back to the original recipe.

“It was a consumer revolt,” said Dworsky. “The company listened; they lost.”

[ad_2]