A celebration of Black military heroism comes to Inglewood

[ad_1]

During World War I, Black soldiers like David Brewer’s grandfather were not allowed in combat. Instead, they lugged cargo, dug trenches and buried the dead for the U.S. Army.

But as the Western Front continued to churn out the dead, France welcomed a group of Black Americans in 1918 to fight under their country’s banner.

The group became known as the Harlem Hellfighters — one of the most renowned Black regiments in history.

Brewer’s grandfather Sylvester Calhoun didn’t fight, but he helped the estimated 4,500 Black soldiers in France who turned the tide of the war.

In 2014, Brewer, a retired vice admiral in the Navy — only the fifth African American to attain the rank — flew to France with his 94-year-old mother so she could see where her father had served with her own eyes.

Actor Dennis Haysbert, left, moderated the panel of retired military leaders including the Air Force’s Lt. Gen. Stayce Harris and Maj. Gen. John F. Phillips, speaking.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

The pair found delight at the sounds of jazz on city streets — just one influence of the Black soldiers who came to France for the Great War.

During World War II, Brewer’s uncle fought in the U.S. Army in Italy. Brewer’s father did not see combat during his service, but settled in Tuskegee, Ala., for his studies.

“His classmate,” Brewer said, “was Gen. Chappie James” — the first Black man to become a four-star general in any U.S. military branch.

Former lawmaker Mark Ridley-Thomas, right, chats with retired Navy Vice Adm. David Brewer, center, and Marine Corps Reserve Maj. Gen. Leo V. Williams III after the panel discussion.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

On Wednesday, as Veterans Day neared, Brewer and five other Black military leaders brought their stories to SoFi Stadium in Inglewood. They spoke about the long and rich history of Black service members.

“Believe it or not,” philanthropist Bernard Kinsey said, many Black soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their heroics in the the Civil War.

And Black troops — “‘colored,’ we were called then,” Kinsey clarified — “dominated getting recognized until Jim Crow.”

The Veterans Day panel was organized by Kinsey’s family, renowned as art collectors. The event included a tour of the historic art, poems and artifacts — like a 1924 photograph of 28 Black Los Angeles firefighters — from the Kinsey Collection that will hang in the halls of SoFi until March.

The heroics of Henry Johnson, who earned the nickname “Black Death” in May 1918, were highlighted at Wednesday’s event.

Fighting on the edge of France’s Argonne Forest, Johnson saved a fellow soldier from capture using grenades and his rifle as a club. And using a bolo knife, he prevented a German raid from reaching his French allies.

Overseas, Johnson and compatriot Needham Roberts received the Croix de Guerre — France’s highest award for valor. But back home in America, the Army refused to recognize Johnson, who was wounded 21 times in the battle.

Discharge records did not mention his debilitating injuries, and the Army would not award him a Purple Heart.

Johnson died in 1929 at the age of 32 of myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle. In 2015, President Obama posthumously awarded Johnson the Medal of Honor.

Although Johnson’s bravery overseas didn’t immediately ease the hardships that he and his peers faced when they returned home, he helped pave the way for prominent commanders in years to come.

In 1940, Benjamin O. Davis Sr. became the Army’s first Black general.

But the belief that Black people could not succeed as officers, or sailors, lingered for years more, Brewer said. In 1944, naval commanders finally launched an officer training course for 16 of the estimated 100,000 Black sailors in the U.S. Navy.

Every one of them passed the course, according to Navy records.

But only 12 were selected as officers. A 13th was made a chief warrant officer, resulting in the group’s nickname: “The Golden 13.”

Twenty-eight years later, in 1970, Brewer joined the Navy, which at the time had no Black admirals.

There were only a few hundred Black officers among the Navy’s 82,000 officers, Brewer said.

“And only five – five — Black sailors had achieved the rank of Navy captain by 1970,” he added.

This year marks 75 years since the U.S. military desegregated, and the numbers still aren’t where they should be, according to the panel of prestigious Black officers.

As Brewer told it, President Truman only integrated the military after Isaac Woodard, a young Black Army sergeant, was dragged off a Greyhound bus on the way home to South Carolina after serving in World War II.

Still in uniform, just hours after being honorably discharged, Woodard was beaten blind and arrested.

The panel of retired military leaders gave credit to the Black service members who came before them and made it possible for them to become high-ranking officers.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

“It was in my wife’s hometown — [in] Fairfield County, South Carolina,” Brewer shared with veterans, students and dignitaries who traveled from as far as Washington, D.C., for the panel.

The country was outraged, and in July 1946, Truman issued Executive Order 9981, abolishing discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin in the United States armed forces.

Even then, it took six years for the Army to fully integrate, said Maj. Gen. Thomas Bostick — a Black commanding general of the Army Corps of Engineers.

Bostick’s father was an orphan at 8 years old, living in Brooklyn, moving from foster home to foster home. “He never really had a family,” Bostick said, until he joined an all-Black unit in the Army at age 17.

He was able to move up the ranks to master sergeant, serving for more than two decades.

“Can you all imagine doing anything for 26 ½ years?” Bostick asked a group of Junior ROTC cadets from John C. Fremont High School in South Los Angeles.

Maj. Gen. Leo V. Williams III of the Marines remembered his father served as a steward in the Navy for 38 years “and retired as one of the senior Black enlisted folks in the Navy.”

The Marine Corps, on the other hand, “was so far behind the other services that you can’t even begin to compare,” Williams said.

When his now ex-wife told her father that she’d be marrying a Black Marine Corps officer, “he said, ‘He’s a liar,’” Williams recalled. “That was 1970.”

“It’s a history that we have crawled our way slowly forward,” he added. “But you have to understand the history to understand how difficult it may be to make moves based on the culture of your institution.”

Williams bid farewell to the Junior ROTC Marines with a ringing “Oorah” as he departed the stage.

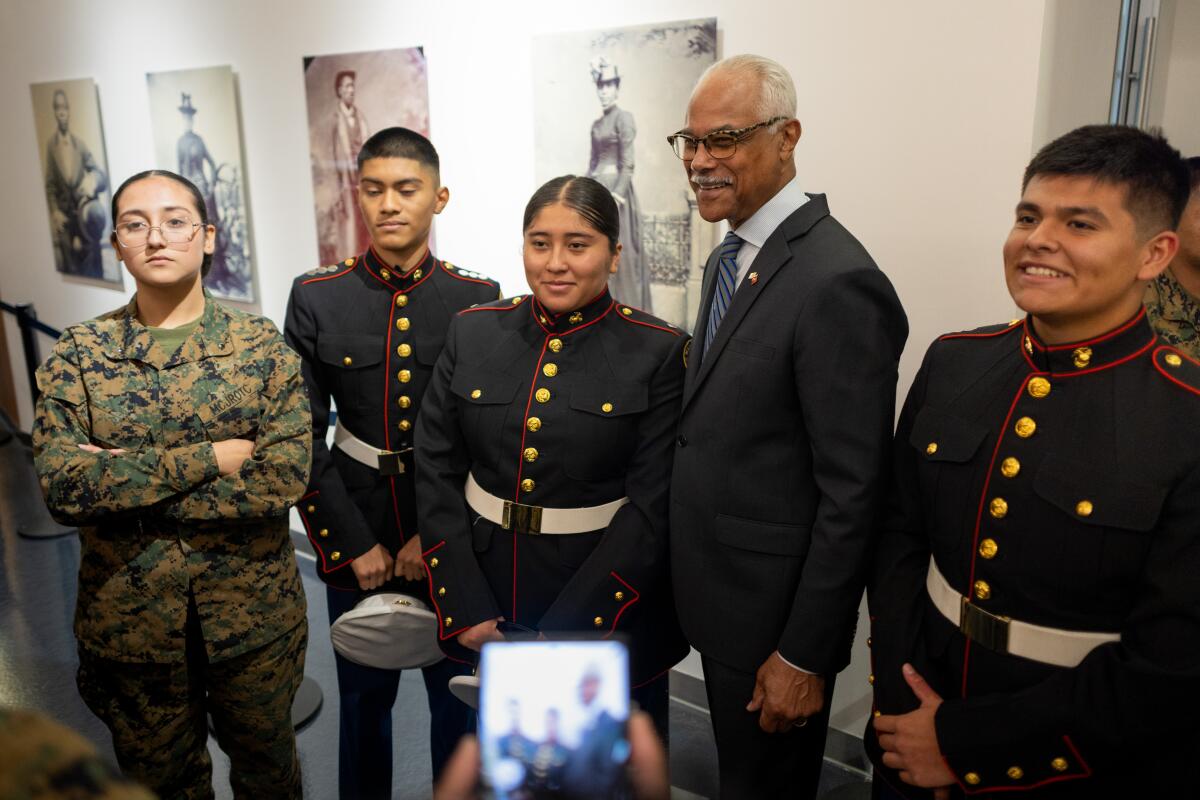

Ruth Murcia, left, and fellow Marine Corps Junior ROTC students from John C. Fremont High School join retired Maj. Gen. Williams, one of the panelists, at the exhibit of items from the Kinsey Collection.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times)

Ruth Murcia, a junior at Fremont High, waited for a chance to speak with Williams. The silver lieutenant discs on her uniform collar quickly caught his eye.

Her family background is steeped in military tradition, but Murcia fears the journey won’t be as easy as loved ones make it sound. She explained that she’s on the fence about joining the armed forces.

Williams advised Murcia to head into the military as an officer, a path made possible by ROTC programs across the country.

Army and Air Force leaders recognized the potential of Black recruits and began placing ROTC units at historically Black universities like Howard as early as 1917. But the Navy refused to host a program of its own until President Lyndon B. Johnson forced the issue in 1968, Brewer said.

The president, a native Texan, placed the unit in his home state at Prairie View A&M.

In 1970, Brewer became one of 13 graduates in the university’s inaugural ROTC class.

“We call it the Prairie View Naval ROTC Golden 13,” Brewer said. “It’s ironic how history repeats itself.”

Bostick, having served as the Army’s head of personnel, said he didn’t aspire to join the military as a child growing up in Japan and Germany.

College was his calling.

“I watched my dad fight two wars. He was always away,” Bostick said. “I didn’t want to do that.”

Bostick fortunately found an ally who helped him become one of six Black engineers out of 4,000 graduates at West Point to complete their coursework.

“In 221 years, there’s been one Black chief of engineers from West Point. That’s me — I don’t know how I got there,” Bostick said with a chuckle.

After 38 years of service, the Army tapped Bostick to address the lack of diversity in the Corps of Engineers, he said.

Bostick called 25 generals into a room to see whom he could promote. There was one white woman, and he was the lone Black face in the room.

He then called in 42 colonels.

“There’s one Asian and there’s one Black female,” Bostick said.

Then he said: “Give me the top 25 captains.” There was one Black man and one white woman.

“So then I go back to West Point, and I’m welcoming 127 cadets that picked the Corps of Engineers. There’s two Black males,” Bostick added.

He wryly told the Army that he estimated he’d have the diversity problem fixed by 2048.

[ad_2]