To understand Seattle’s toilet crisis, take a ride through the city

[ad_1]

You can ride 45 minutes through Seattle on light rail, from Northgate through Rainier Beach, without access to an in-station public restroom. When you stroll into some of the city’s busiest neighborhoods, your options don’t get much better. Why are restrooms scarce — and what are the consequences? We went looking for answers. Scroll along to experience that journey.

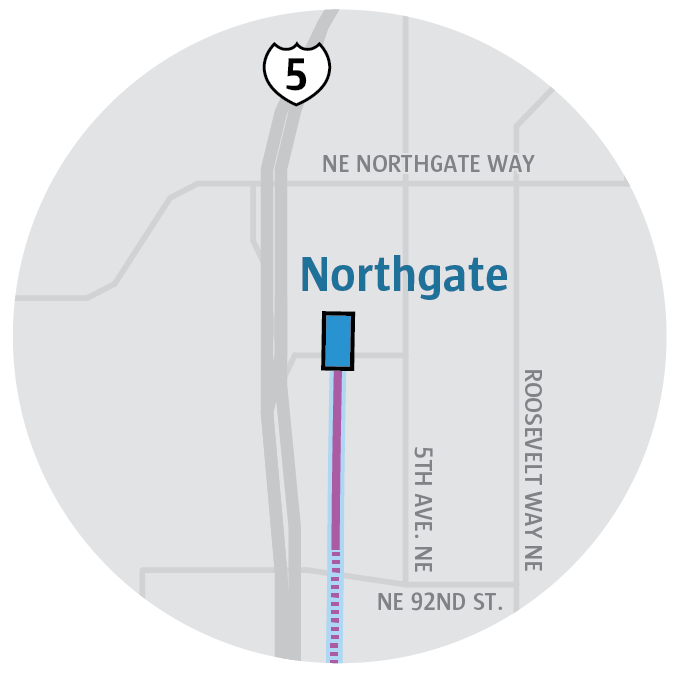

Northgate

As his bus arrived at the Northgate light-rail station, William Sandoval prayed one of the Honey Buckets placed below the station would be usable. Earlier that day, when he initially passed through, the green stalls were in bad shape.

“Toilet paper all over the floor. Excrement and urine everywhere,” said Sandoval, 75, returning home from shopping in Lynnwood.

This time, the mess was gone, so the University District resident could make a pit stop. But most restroom prayers uttered by transit riders go unanswered. King County Metro operates no toilets at all in the city, and only one Sound Transit light-rail station in Seattle proper includes restrooms.

That station is Northgate, where the stalls were subjected to repeated vandalism after opening in 2021 and where renovations this summer forced riders to use porta-potties. The station’s actual restrooms are reopening soon, with a change. You’ll have to get buzzed in via camera from Sound Transit’s headquarters.

Sandoval blames Seattle leaders, saying they should do more to help people who wreck restrooms and to deter bad behavior.

“Do it with a bit of heart, but please put an end to this,” he said. “We all deserve to be able to go.”

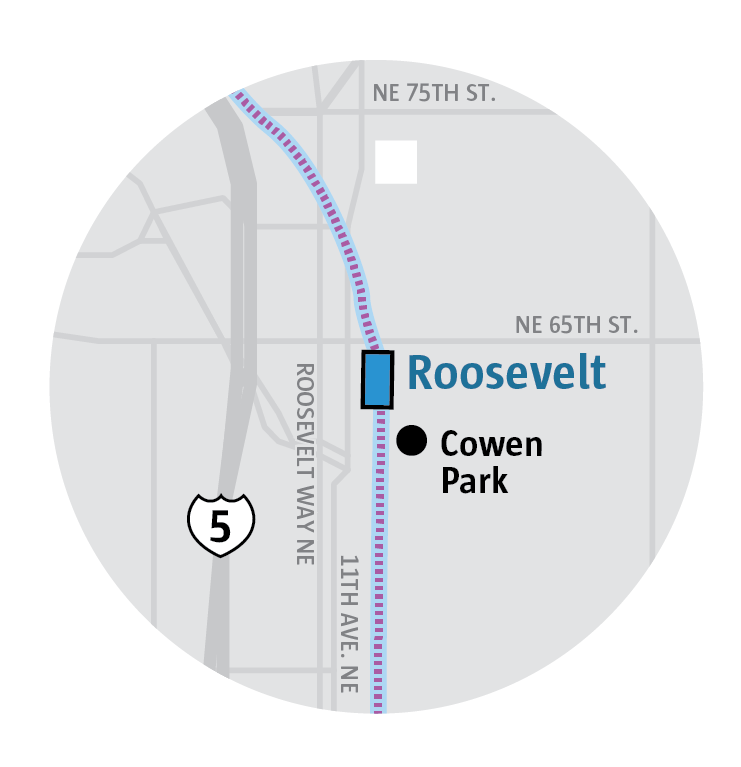

Roosevelt

Restroom worries add to Janelle Newell’s mental load whenever she and her son leave home, she said at Cowen Park, near the Roosevelt light-rail station.

They mostly visit playgrounds at community centers, because the centers have restrooms where Newell feels comfortable changing 2-year-old Jeremiah’s diaper and washing his hands. The toilets in Seattle parks are often closed, dark or dirty, she said.

“He gets pretty intimidated,” said Newell, a Wedgwood resident.

She didn’t take her water bottle on their trip to Cowen Park, because she “assumed I wouldn’t be able to go.” And she calculated how long it would take to push Jeremiah’s stroller to the nearest community center, a mile away. Cowen Park’s restrooms were closed when she and Jeremiah showed up.

“It’s a big deal” said Newell, 32. “I have to plan accordingly.”

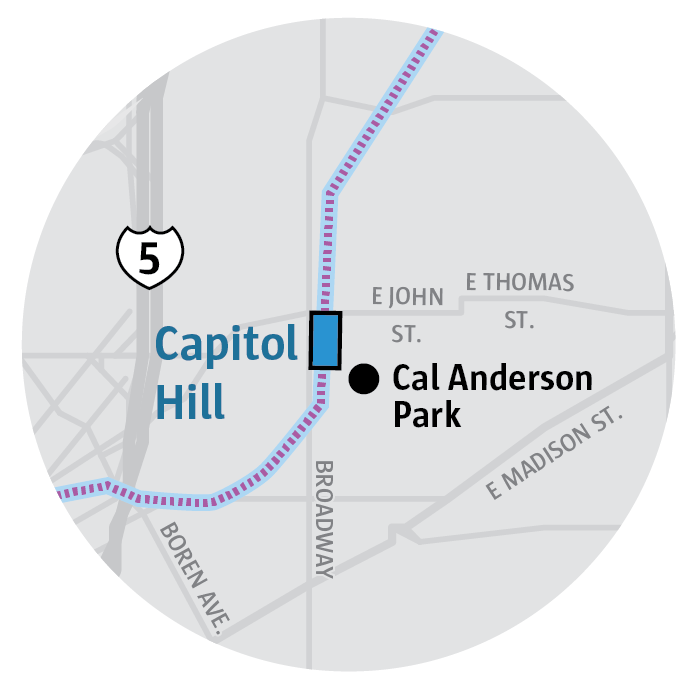

Capitol Hill

“What’s behind Door Number 1, Deb?” Remy Shannon called out.

“What did we win today?”

Shannon and Deborah Amituanai, maintenance workers for Seattle Parks and Recreation, were joking around before cleaning a restroom on Capitol Hill. Many times, what they “win” at Cal Anderson Park is pretty gross.

“Poop on the floor. Vomit everywhere. Lots of trash. Discarded clothes. Drugs. Drug paraphernalia,” Shannon said. “We use litter sticks. We don’t touch anything with our hands, even wearing gloves.”

The workers are part of a push to improve conditions in park restrooms, with the city spending more money on renovations and maintenance. Decked out in water-repellent gear, they sweep the concrete floors, unclog the toilets, spray blue sanitizer and blast gunk away with pressure washers.

“It’s not an easy task but we enjoy doing it because we like to make it clean,” Amituanai said.

Some of the toughest restrooms are those used by people using drugs, coping with mental illnesses and living outside, Shannon said. People sleep or overdose in the stalls. Start fires. Leave needles in toilet paper holders.

Still, Shannon believes open access is crucial. People take shelter and do drugs in the restrooms because they don’t have safer options, the Parks worker said. Providing those “could fix a lot of these issues,” Shannon said.

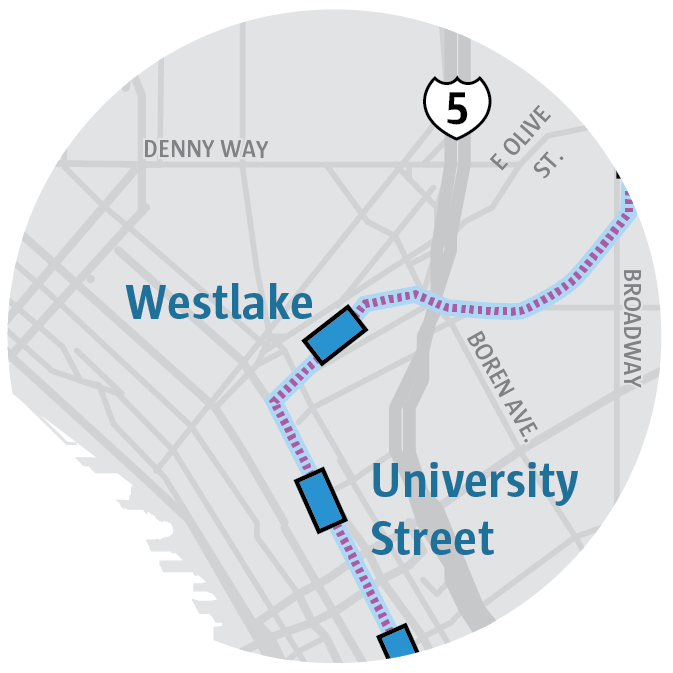

Westlake

When tourists step off the light rail at Westlake Station and ask Dion Hardeman where to use a restroom, the transit ambassador wishes he could be more helpful. But there are no permanent public restrooms in the heart of downtown Seattle.

Hardeman sometimes recommends Starbucks or Nordstrom. Pike Place Market is several blocks away. Something he doesn’t mention: Many locals end up “using the street.”

That’s the sad reality, agreed Michelle Clise, who’s lived on Third Avenue for decades. It’s not only homeless people who go outside.

“I see guys in three-piece suits peeing in the alley,” she said.

Hoping to avoid an accident with her granddaughter who had to go, Nercelia Jackson was shocked when three downtown businesses turned them away.

“Everybody was saying, ‘Just go to Pike Place,’” the Southern California tourist said, standing outside the Market’s crowded restrooms. “We’re hoping she doesn’t pee on herself right now.”

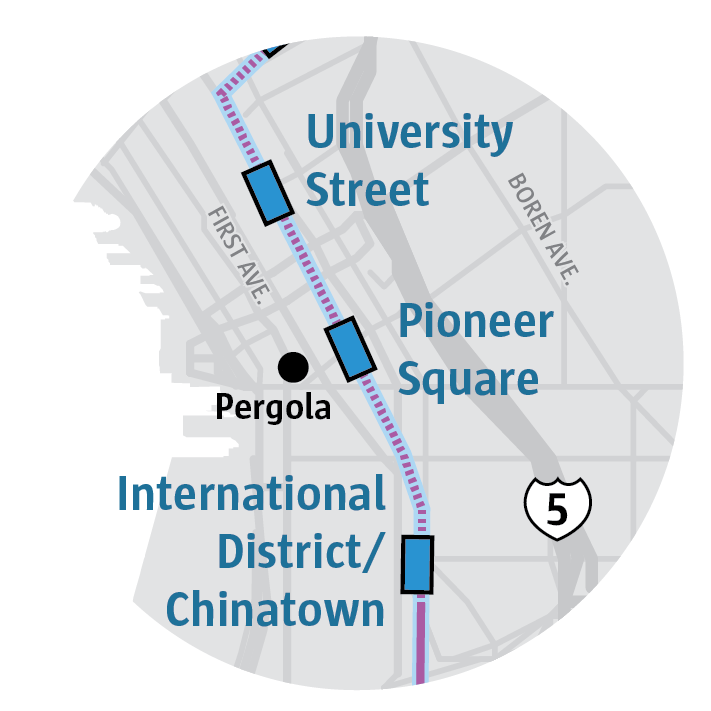

Pioneer Square

The tour groups walking by Pioneer Square’s black iron pergola don’t seem to disturb the man who’s curled up asleep on a bench under its cover. It’s a clear morning in this small, quiet park.

Early in the city’s history, Pioneer Square’s water supply came in the form of exposed hollowed-out logs, and at the same time, waterborne diseases like cholera were prevalent, said Josephine Ensign, author of “Skid Road,” about Seattle’s history of homelessness.

In 1909, one of the city’s earliest public health improvements was an underground restroom in Pioneer Square. Located below the pergola, with marble stalls and white-tiled walls, it was known as “The Queen Mary of the Johns.”

This ruffled many feathers, according to The Seattle Times’ archives. The concerns are “echoes of what we hear today,” Ensign said — like how do you ensure they’re used correctly and who will clean them?

But the pergola restroom proved useful, and was later missed when it closed more than 30 years later during World War II.

It’s capped over now, covered in concrete.

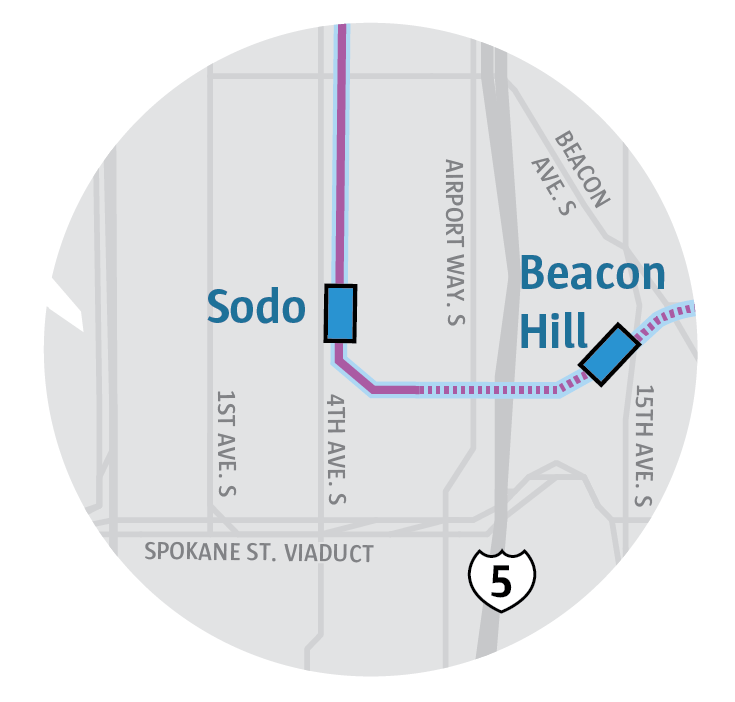

Sodo

If Ashly Weber has to enter a business to use its restroom, she tries to dress up and look like everyone else, she said, standing outside her friend’s rumbling RV in Sodo on a warm day.

Homeless on and off for almost half her life, the 32-year-old says success can depend on how you appear. Many business owners, wary of Seattle’s long homelessness crisis and related problems, have restricted their restrooms, hoping to avoid trouble. What’s left for the city’s poorest residents is limited, gross or hard to count on.

“Trying to find a bathroom downtown is near impossible,” Weber said.

At the same time, Seattle has fallen behind other West Coast cities on providing restrooms specifically for people living outside.

Living around the Sodo and Georgetown area, Weber said her chances of finding an unlocked porta-potty go up in the industrial zones.

But she knows there’s danger in that, too.

In 2017, after using an unlocked porta-potty next to train tracks in Georgetown, Weber said she exited and was met by a police officer, who informed her she was on private property. She was arrested, charged with trespassing and spent a night in jail, she said.

The charges were later dropped.

Beacon Hill

It’s not uncommon for Luis Rodriquez to get a call from The Station, the Beacon Hill coffeeshop he owns, when staff members need his help.

The calls are usually related to work behind the counter, but about two dozen times, Rodriquez estimates, they’ve been about something else.

“There’s a person in the bathroom and can you please come? We’re slammed.”

If the shop’s only restroom is locked for upwards of an hour, it can cause serious problems for the small-business operator and his anxious customers waiting in line. Rodriquez said he’s lost customers over it.

His and other stores surrounding Beacon Hill’s busy light-rail stop face pressure to open their toilets for passersby, because there are no public restrooms in the station itself. There are some in the Beacon Hill library, but that’s a three-minute walk away.

“We are a very inclusive business,” Rodriquez said. He doesn’t require people to buy an item in order to use the toilet. Sometimes that means people enter his bathroom to use drugs in private or clean themselves in the sink if they’re living outside.

Typically, people will come out if he keeps knocking and talking to them. Only once has the Fire Department had to break down the door, Rodriquez said. Thankfully, he said, that person was still alive.

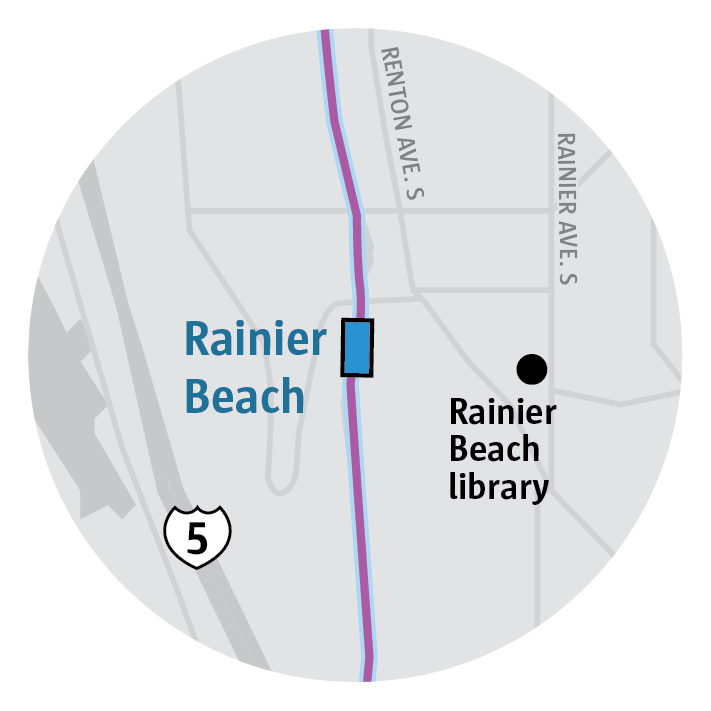

Rainier Beach

Inside the Rainier Beach library, children were lounging in the kid’s section reading, enjoying the last week before school starts. Adults were hunched over computer screens. And two were standing in the entryway, right next to the bathrooms, charging their phones and keeping watch over their belongings.

Jeffrey Stephenson was one of them.

The 32-year-old stops by around noon every day to use the library’s restroom, get out of the elements, and research his interests — like how diamonds are made and how to identify the stones he finds.

He doesn’t come solely for the hygiene resources, but unlike private businesses, it’s free and there’s no guessing if he’ll be denied a key to the bathroom. Seattle’s 27 library branches play a critical role for providing public restrooms because they’re open to everyone, spread throughout the city and with reliable hours.

“It’s the place where I feel most safe,” Stephenson said.

He used to take the city bus there when he was in the first grade, he said. He liked reading the “Goosebumps” series and “Harry Potter.”

Now homeless and living in a park, Stephenson’s journey to the Rainier Beach branch looks a little different these days — he pushes a shopping cart and carries around 50 pounds on his back. But the library’s doors — and restrooms — still open for him just the same.

[ad_2]