Valley fever is on the rise in the U.S., and climate change could be helping the fungus spread

[ad_1]

More than 500,000 Americans could be sickened each year by Valley fever, the disease caused by breathing in the fungus Coccidioides, according to preliminary estimates developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The draft figures, which were disclosed in a CDC presentation to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, suggest the toll inflicted on Americans by the fungus could be more than triple the size of widely cited previous estimates.

“There’s just not a ton of awareness or knowledge about the disease. We do see a lot of travel associated cases, we’ve seen reports of cases popping up in places where we wouldn’t have typically expected Valley fever to be endemic,” Samantha Williams, an epidemiologist with the CDC’s Mycotic Diseases Branch, told CBS News.

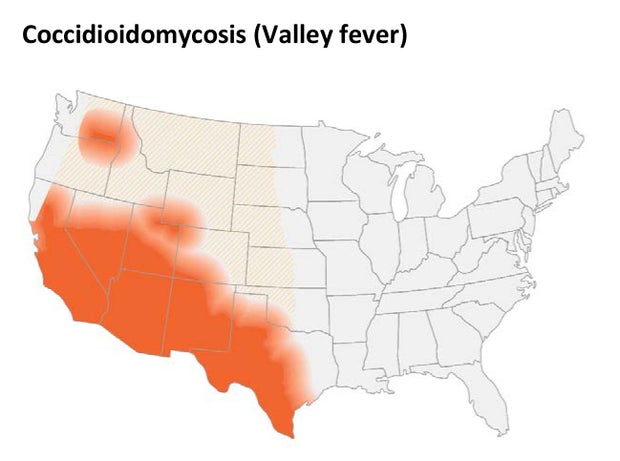

Williams is part of the team that has been refining these forthcoming estimates of cases of Valley fever, which scientists call Coccidioidomycosis. It is one of a range of new projects aimed at ramping up the agency’s response to the illness, which primarily occurs in the Southwest, from California to central Texas.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Though only a fraction of cases each year are reported to the CDC these tallies have also been rising: preliminary figures topped out at 20,197 cases reported through the end of 2021, the most on record in a single year since the last peak of cases in 2011.

In states where the fungus has historically caused the most hospitalizations, officials have been warning of signs of increased risk.

“When you compare the numbers now and in 2021 to 2014, they’ve increased pretty drastically since then. Within Arizona, it’s basically doubled, and within California, more than tripled,” Williams said.

What are the signs and symptoms of Valley fever?

Symptomatic cases of Valley fever often start mild, with signs similar to influenza or COVID-19 like fever, cough, and rash. People may also experience headaches, fatigue, night sweats, and muscle aches or joint pain, the CDC says.

Symptoms typically develop between 1 and 3 weeks after breathing in spores of the fungus, which occur naturally in the soil of some Western states, primarily across the Southwest.

While some people can recover on their own, dangerous complications can develop in as many as 10% of cases, the CDC says.

“Even with mild disease, it can still produce illness that last for weeks, unnecessary healthcare visits, time missed from work or school,” said Williams.

While identifying cases has improved in recent years, Williams said many doctors — even in areas where Valley fever is more common — can sometimes take months to correctly diagnose cases. Instead, time can be wasted resorting to treatments like antibiotics that do not work for Valley fever.

That hurdle can be magnified when people catch the fungus while traveling, then try to seek treatment after they are back home from doctors that may never have seen Valley fever cases.

“Recognizing it early to treat it early is really important,” said Williams.

What precautions should I take?

Officials acknowledge it is difficult to avoid catching Valley fever in areas where the fungus is endemic, given how spores can spread through the air.

In California, the state urges residents in areas with high rates of infections to mitigate dust stirred up by digging and minimize time outdoors during windy and dusty days.

People at higher risk of severe disease can wear N95 masks to cut down on their exposure if they have to be outdoors.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America also recommends considering some preemptive treatments for especially vulnerable patients, like organ transplant recipients.

What are the options for treating Valley fever?

Most recommended treatments for Valley fever rely on “off-label” unapproved uses of drugs the Food and Drug Administration has only approved for other fungi, though federal agencies have sought in recent years to foster new options for doctors.

“Coccidioidomycosis poses a major threat to public health in endemic regions, yet no vaccine has been developed, novel effective therapies are lacking, and drug development had stalled until recently,” the FDA reported last year, from a recent workshop convened to discuss Valley fever.

The National Institutes of Health has also awarded new grants designed to encourage more scientists to focus on Valley fever, and it plans to encourage development of a vaccine to prevent the fungus. Promising potential vaccines have been tested in animals.

“Because Coccidioides infection in people usually provides protective immunity from reinfection, developing a safe and effective vaccine is generally thought to be feasible and would be expected to provide durable immunity,” a working group convened by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases wrote in a “strategic plan” released last year.

How is climate change linked to Valley fever?

“California’s dry conditions, combined with recent heavy winter rains could [result] in increasing Valley fever cases in the coming months,” California’s state health department warned in a news release Aug. 1.

The department cited recent research linking climbing transmission of the fungus to increasing cycles of drought across the Southwest — just one of several growing health threats linked to climate change. Other research has also linked upticks in the fungal infections to exposure to smoke from wildfires.

Warming temperatures and changes in rain patterns are also projected to substantially widen the map of where the fungus thrives, beyond the areas where cases are already mounting.

“The area we considered endemic, meaning the fungus can live in the soil, continues to move further north as the climate changes and gets a little bit warmer,” Dr. Stuart Cohen, co-director for the Center for Valley Fever, told CBS Sacramento.

So far, likely cases of local-acquired Valley fever infections have been reported across a broad swath of the West, from Texas up to Washington state.

“We want people to understand, and especially clinicians to understand, that these maps are not set in stone, right? And so even within the map, there are pockets of greater endemicity and lower endemicity, but it also could occur outside of those areas,” said Williams.

[ad_2]